KARACHI, Apr 21 (IPS) – When Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi visits Pakistan this week (April 22, 2024), experts say the two issues topmost on his mind that he will want to discuss with his Pakistani counterpart, President Asif Ali Zardari, will be border security and the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline.

“This visit comes at the most troubling time for the region,” said Senator Mushaid Hussain Sayed, chairman of the Islamabad-based Pakistan-China Institute, pointing to the war in Gaza and the resurgence of terrorism from Afghanistan, which borders both Pakistan and Iran. Added tension comes after retaliatory strikes by Israel and Iran. A suspected Israeli strike on an Iranian consulate in Syria at the beginning of the month was followed by a retaliatory attack by Iran on Israel on April 13. US officials say Israel responded, despite a plea by UN Secretary-General António Guterres for restraint.

The gas pipeline will be an uneasy conversation to hold for Zardari, but with the lives and livelihoods of over 240 million Pakistanis tied to this fuel, finding a solution is of paramount importance for the rulers.

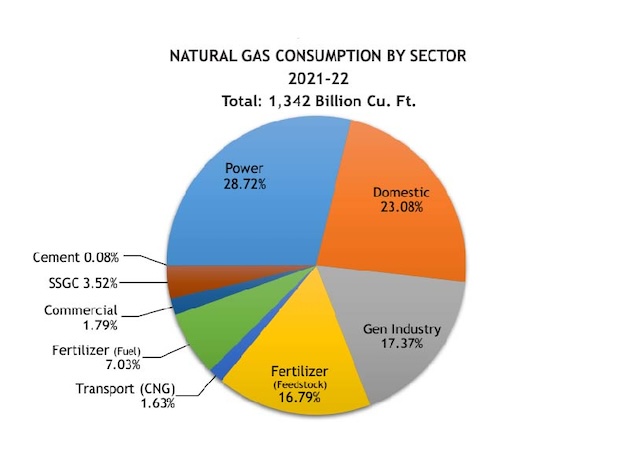

Pakistan needs gas more for residential, commercial, and industrial purposes now than for power generation, said energy expert Vaqar Zakaria, heading the Islamabad-based Hagler Bailley Pakistan, the environment consultancy company.

“Domestic consumers will be the immediate beneficiaries from the Iranian gas supply,” agreed leading sustainable development practitioner Abid Suleri, heading the Islamabad-based Sustainable Development Policy Institute. He also said the country’s economy will flourish manifold if the industry receives a steady supply of this gas.

Zakaria had been part of the negotiations some 25 years ago, in the 1990s, when conversation on importing gas from Iran through an Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline first started due to the fact that “our gas reserves were fast depleting because we were using up this finite resource as if there was no tomorrow. People would leave the stove on for hours instead of turning off the gas,” Zakaria said, blaming the lackadaisical attitude of the people and the visionless government policy of selling it at “dirt cheap rates to keep the voters happy.”

There was a third partner, India, which decided to exit in 2009, “citing pricing and security issues, and after signing a civilian nuclear deal with the United States in 2008,” Zakaria recalled.

“Iran has huge energy reserves such as crude oil and natural gas and is ready to meet the needs of friendly and neighboring countries,” said Hassan Nourain, the consul general of Iran in Karachi, in an interview to IPS. In 2021, it was estimated that Iran had close to 1,203 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, the second largest after Russia.

Pakistan and Iran continued negotiating, and on May 24, 2009, the project was signed by the Pakistani president, Asif Ali Zardari, and the Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, for the supply of gas ranging from 750 million ft3/d to around 1 billion ft3/d, for 25 years, from the South Pars gas field in Iran and delivered at the Pakistan-Iran border, near Gwadar.

The project, having a pipeline length of 1,150-km within Iran and 781-km within Pakistan, was to be constructed by each country in their respective territories. Iran completed its side of pipeline construction by 2012 and was ready to transport gas to Pakistan by 2015, the Nourain said. Pakistan did not start until 2013.

A year later, in 2014, Pakistan’s petroleum minister, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, told the Iranian government that due to sanctions on Iran, banks and contractors were unwilling to go ahead with the project on Pakistan’s side.

Ten years later, Pakistan is toying with the idea of building the pipeline again and in February of this year, Pakistan’s caretaker government approved the construction of the first 80-kilometer stretch from the Iranian border to Gwadar in Balochistan.

Donald Lu, US Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia, immediately censured Pakistan for its plans to import gas from Iran, as it would expose Pakistan to US sanctions.

“If a neighbor is giving us gas at competitive rates, then it is our right ,” Pakistan’s Defense Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif told the media earlier this month.

“The threat of these unilateral sanctions imposed on Iran by the US is illegal,” said Nourain. “In 2006, the United Nations Security Council demanded Iran halt its uranium enrichment programme and imposed certain sanctions but after monitoring it, in 2016, most sanctions were lifted for at least ten years.”

But, pointed out Arif Anwar, an international development practitioner: “The US is entitled to do what it wants with USAID and or any banks, businesses and insurance companies that operate in the US. The sanctions on Iran and on countries trading with it have been around for decades and may even have some UN legitimacy cover.”

Moreover, warned Anwar, given that Pakistan needs support from the International Monetary Fund, which would also require US support, “Pakistan needs to tread a careful path.”

“Pakistan needs gas,” said Lahore-based lawyer Ahmad Rafay Alam, terming the US warning “an unfair US policy.”

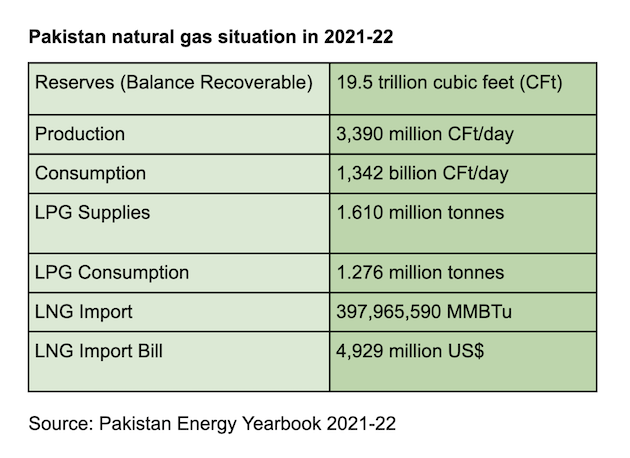

“The pipeline is pivotal for Pakistan’s energy independence,” pointed out Sayed. “It cuts costs as it is 40 percent less than imported LNG (liquefied natural gas),” he said.

“The US no longer has the moral authority to impose sanctions on either Iran or Pakistan if both countries exercise their sovereignty and agree to buy and sell anything to one another, not after its support of the Gaza genocide,” Alam said, echoing the sentiments of a vast majority of the South Asian nation of over 240 million that remain staunch supporters of Palestine.

But, said Anwar, the Pakistani government needs to reflect on how it arrived at this difficult predicament. “The sanctions against Iran were in place well before the contract was signed. Why didn’t the government insert suitable safeguards in the contract?” and then responded to his own question: “Because political expediency takes priority.”

He was referring to the quandary that Pakistan is in right now—if it does not build the pipeline, Iran can slap a fine of USD 18 billion. The deadline expires in September this year. And if it goes ahead, the US may place sanctions on Pakistan.

“The government of Pakistan asked Iran to extend the timeline in 2014 for ten years and that expires this year,” the Nourain pointed out.

Seeking Waivers

However, there is one option left for Pakistan. “We start with the Pakistani side of the pipeline, and in the meantime, we officially seek a waiver as well,” offers Sayed.

Former Law and Justice Minister Ahmad Irfan Aslam said taking the diplomatic route and seeking support from Saudi Arabia and the UAE may secure Pakistan a waiver, but warned: “In return, the US will have its own set of demands.” It will mean treading smartly and “constructing a package that works for both sides,” he told IPS.

But with the hostile US-Iran relations, Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute in Washington, said Washington may not be in a charitable mood with countries engaging commercially with Iran.

“It won’t be inclined to give Pakistan a sanctions waiver,” he said.

“Some countries are allowed to import gas and petroleum products from Iran; why can’t Pakistan get the waiver?” countered the Nourain.

China, Greece, Italy, South Korea, Japan, Turkey, Iraq, and Taiwan were given waivers by the US in the past for importing oil from Iran but not extended beyond April 2019, leading to a significant drop in Iran’s oil exports. However, China has continued to import Iranian crude oil and has made it clear that it is not willing to comply with US sanctions against Iran.

“The US applies a double standard,” said Nourain, adding: “When the US warns Pakistan of sanctions, it is not on the government, but on the people of Pakistan.”

“We should insist on the same rules for Pakistan as there are for others regarding importing energy from Iran,” Sayed said.

The US mission in the country told IPS that Pakistan has not requested a waiver.

But if Pakistan pursues the pipeline project, Zakaria pointed out that it may find it difficult to look for funders.

Kugelman believed Beijing could be wooed, but Moscow could also be an option. “With Russia enjoying friendly relations with Iran, if the former can help Pakistan on this, Pakistan-Russia relations will also gather strength,” he added.

Anwar had an alternative perspective. “If countries can engage their private sector for space travel, surely Pakistan can do it for a gas pipeline,” he said. “The agreement may be government-to-government but the private sector could manage construction and operation,” he said. “The government should not try everything itself, but rather create an environment for the private sector to invest and deliver goods and services.”

Or, pointed out Kugelman, “Pakistan may focus more attention on legal avenues that bring down the risk of facing a massive fine if it doesn’t end up building it.” He admitted that none of the options were good or easy. “It’s one more policy conundrum for a new government grappling with plenty of them.”

Imported Gas or Domestic Renewables?

Pakistan is getting LNG at USD 13/MMBTu through long-term contracts, while the spot market is currently trending around USD 8/MMBTu. So, Pakistan should negotiate firmly with Iran on pricing to buy it at a “considerably cheaper price for it to make sense for Pakistan to build the pipeline and transport the gas across Pakistan,” said Haneea Isaad, energy finance specialist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

And with predictions of a “supply glut” from 2025 onwards, she pointed out, the price of LNG is expected to continue the downward trend.

Suleri had the same advice. “Securing affordable LNG, irrespective of its source, is Pakistan’s best bet.”

However, Isaad warned that an unprecedented hot or cold spell in Europe and East Asia may “lead to a hike in LNG prices right back in and should be factored in.”

Others ask that if Iran goes off the charts again, perhaps Pakistan can look to Central Asia for supplies of natural gas, to which the US should have no objections. Last year, Islamabad and Ashgabat signed a joint implementation plan to revive the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline project, which aims to export up to 33 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year through a proposed approximately 1,800-kilometer pipeline from Turkmenistan to India. “TAPI will not take off until Afghanistan and India do not come on board, and frankly, in the current geopolitical mess that we’re in, this is not going to happen anytime soon,” said Suleri.

With the challenge of ensuring a steady supply of gas at an affordable price and the looming threats of sanctions and penalties from Iran, Suleri also reminded us that Pakistan’s pledge to shift to 60 percent renewable energy by 2030 was just six years away.

“We can switch to solar water heating in homes, like it is done in Kathmandu, instead of using natural gas, with backup electric water heating when the weather is cloudy,” suggested Zakaria. Electricity can also be generated in homes using solar panels, he added. “And instead of expanding the gas network to smaller towns at a high cost, LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) can be cross-subsidized with gas to provide cleaner fuel to houses at an affordable price.”

“Pakistan should look into investing in REs,” agreed Suleri, but pointed out that it may not be commercially viable to supply at a scale that meets the country’s requirements.

IPS UN Bureau Report

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2024) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service