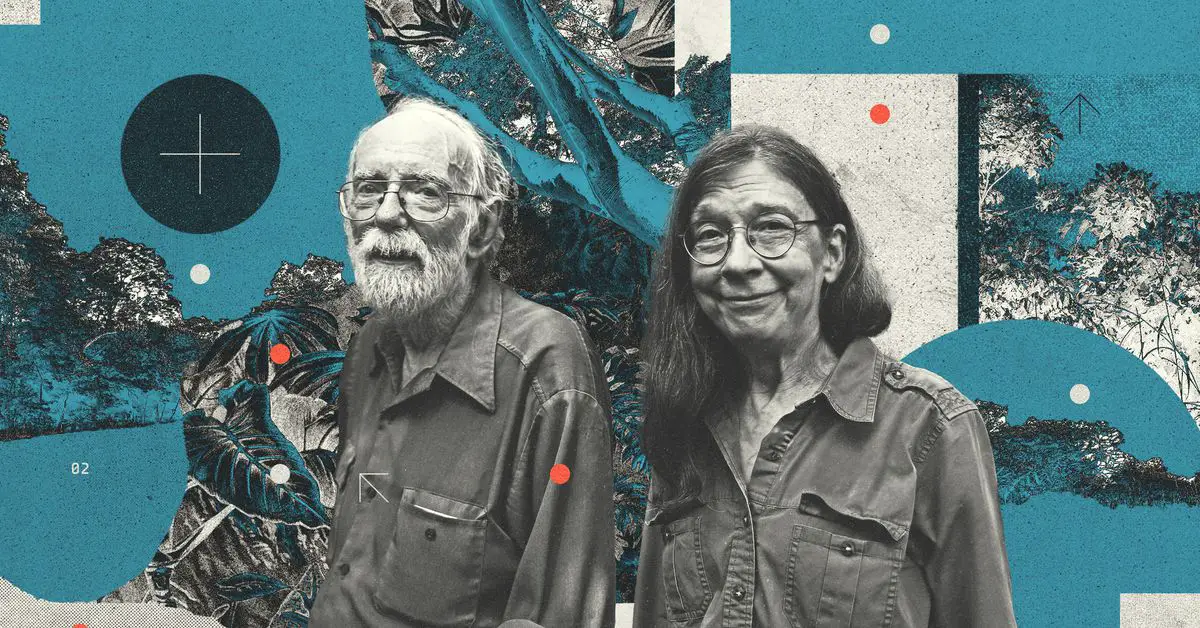

Ecologist Daniel Janzen wades into the field, clutching a walking stick in one hand and a fist full of towering green blades of grass in the other to steady himself. Winnie Hallwachs, also an ecologist and Janzen’s wife, watches him closely, carrying a hat that she hands to him once he stops to explain our whereabouts.

Together with other conservationists who have dedicated decades of their lives to this place, the couple has brought forests back to the Area de Conservación Guanacaste (ACG). It’s an astonishing 163,000 hectares of protected landscapes — an area larger than the Hawaiian island of Oahu — where forests have reclaimed farmland in Costa Rica.

The grass isn’t supposed to be here. Janzen and Hallwachs only keep this small field around as a reminder of — and to show visitors like me — how far they’ve come since the 1970s, when pastures and ranches still dominated much of the landscape.

Across from the field, on the other side of a two-lane road that winds through the ACG, is one of the first stretches of young forest that Janzen and Hallwachs started nursing back to life. Tree limbs stretch out over the road, as if trying to reach the remaining patch of grass left to seed on the other side.

“This is just weird.”

ACG is a success story, a powerful example of what can happen when humans help forests heal. It’s part of what’s made Costa Rica a destination for ecotourism and the first tropical country in the world to reverse deforestation. But now, the couple’s beloved forest faces a more insidious threat.

Across the road, the leaves are too perfect. It’s like they’re growing in a greenhouse, Janzen says. There’s an eerie absence among the foliage — although you’d probably also have to be a regular in the forest to notice.

“Every year it seems worse,” Hallwachs says. “We should have found bugs.”

There should have been bees, wasps, and moths along our walk, she explains. And plenty of caterpillar “houses” — curled up leaves the critters sew together that eventually become shelter for other insects. “The houses were everywhere, now it’s almost exciting when you see one,” Hallwachs says. “This is just weird.”

The bugs play crucial roles in the forest — from pollinating plants to forming the base of the food chain. Their disappearance is a warning. Climate change has come to the ACG, marking a new, troubling chapter in the park’s comeback story.

It also serves as a lesson for conservation efforts around the globe. More than 190 countries have recently committed to restoring 30 percent of the world’s degraded ecosystems under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Billionaire philanthropists are pledging to support those efforts. What’s happening here in the ACG says a lot about what it takes to revive a forest — especially in a warming world.

“When I was here earlier, a younger person, I could win a case of beer by betting on the first day that the rains would start,” Janzen tells The Verge. Now, at 85 years old, he says, “I would never dream of betting anything because it can start a month early or a month late.”

The dry season is about two months longer than it was when Janzen arrived in the 1960s. Climate change is making seasons more unpredictable and weather more erratic across the planet. And that’s posing new risks to the sanctuary scientists like Janzen and Hallwachs have created at ACG.

María Marta Chavarría, ACG’s field investigation program coordinator, describes the unpredictability as “el alegrón de burro.” Strictly translated from Spanish, it means “donkey happiness.” Colloquially, it describes a fake-out: short-lived joy from a false start.

Chavarría, who speaks with the upbeat tilt of an educator excited to teach, explains it like this, “A big rain is the trigger. It’s time! The rainy season is going to start!” Trees unfurl new leaves. Moths and other insects that eat those leaves emerge. But now, the rains don’t always last. The leaves die and fall. That has ripple effects across the food chain, from the insects that eat the leaves to birds that eat the insects. They perish or move on. And next season, there are fewer pollinators for the plants. “The big trigger in the beginning was false,” Chavarría explains. “They started, but no more.”

In 1978, Janzen jumped down a ravine because he was “young and carefree and just 40 years old,” in his words. Slipping on wet rocks, he broke three ribs. While recuperating, he spent a month sitting outside of his home on the edge of the forest in the evenings. Next to a 25-watt light bulb outside, the “front wall was literally plastered with adult moths,” he recalls in a 2021 paper he and Hallwachs published in the journal PNAS. The title was “To us insectometers, it is clear that insect decline in our Costa Rican tropics is real, so let’s be kind to the survivors.”

That observation in 1978 led the couple to focus their research on caterpillars and their parasites. In 1980, they used light traps to inventory moth species across the country, documenting at least 10,000 species. Since then, however, they’ve seen a steady decline in caterpillars whose feces used to blanket the forest floor.

Hanging a white sheet and lights at the edge of a cliff overlooking a vast stretch of both old and new-growth forests, they photographed moths that came to rest on the sheet in 1984, 1995, 2007, and 2019. The first photograph is an impressive tapestry of many different winged critters. By 2019, that’s been reduced to a mostly white sheet speckled here and there with far fewer moths. Instead of an intricate tapestry of wings and antennae, the sheet looks more like a blank canvas an artist has only started to splatter with a brush.

Hallwachs and Janzen can see the same phenomenon now standing in broad daylight in the forest across from the field. Just because forests have come roaring back across the ACG doesn’t mean the struggle to survive is over.

1/3

How to turn a ranch into a forest

In a roundabout way, butterflies brought Janzen to Guanacaste. A ninth-grade trip to collect butterflies in Mexico sparked his love of tropical ecosystems in the 1950s. He returned to Veracruz, Mexico, as a PhD student a decade later, collecting insects for a research project. Guanacaste is biologically similar to Veracruz, Janzen says — filled with tropical dry forests. The parallels brought him to Costa Rica in 1963 to research interactions between plants and animals.

Compared to rainforests that have cafes and even an e-commerce giant named after them, dry forests arguably aren’t in the spotlight so much. And yet they’re disappearing faster across Latin America than their rainier counterparts. Dry forests are less humid and a little more hospitable to people and agriculture, so people came to raze them. In Costa Rica, which exported as much as 60 percent of its beef to Burger King at one point, ranches and pastures replaced forests. Grasses, good for cows, grew in their place. Between 1940 and 1990, forest cover in Costa Rica shrank from 75 to just 29 percent.

Another American conservationist, Kenton Miller, first envisioned a national park in Guanacaste in 1966. Commissioned by the Costa Rican government to plan a national monument to one of the country’s oldest ranches in the area, he instead made the case for preserving a stretch of Guanacaste’s remaining, albeit damaged, dry forest. The aim was to protect 10,400 hectares of land that’s now the Parque Nacional Santa Rosa. And Miller wanted to do more. Park staff still quote him saying his “dream was the creation of a national park that would stretch from the sea to the peaks of mountains and volcanoes.”

Janzen was ambling around the area around the same time, albeit more focused on research than conservation. “I studied it, they saved it,” he wrote in 2000. Hallwachs joined him as a volunteer research assistant in 1978, and the two married soon after.

In Santa Rosa, Hallwachs studied agoutis, rodents that can get to be about as big as domestic cats. She devised an ingenious way to study how the animals disperse seeds throughout the forest, Janzen boasts proudly, by placing a bobbin of thread inside the thick-skinned fruit of the guapinol tree that agoutis bury to eat later.

The nature of their work started to change in 1985 after a trip to study Australia’s dry forests. There, they saw how ranchers’ fires had caused so much devastation over the years that even some biologists had no idea that what they saw as grass plains were really overgrown pastures that used to be forest. They realized that fires could do the same in Guanacaste, as long as the grass remained.

The problem is sometimes called the human-grass-fire cycle: when invasive grasses, often introduced through agriculture, crowd out forests and then dry out and become fuel, making the landscape more fire-prone. It’s a threat in a lot of places outside of Costa Rica, contributing to the devastating fire that tore through Maui last year.

In Guanacaste, ranchers had wielded fire since the 1600s to keep the forest at bay, preventing it from creeping back into pastures. If Santa Rosa was to survive, fires and invasive grasses would have to go. The national park would also need to grow with the support of the local community.

The couple drafted a plan to expand Santa Rosa into a larger conservation area, enlisting residents’ help in stamping out fires and even hiring former ranch hands to form a firefighting crew. Over 30 years, the initiative to create ACG raised enough money to buy more than 350 surrounding farms and ranches. Serendipitously, by the 1990s, declining international beef prices and a landmark forest law that outlawed deforestation and paid people to protect natural resources also served to transform the landscape across Costa Rica.

It’s a victory that, lately, has been in the shadow of splashy commitments by influencers, billionaires, and policymakers to plant a ton of trees. It’s become a popular way for companies and consumers to try to offset some of their environmental footprint. “We see all the hype coming from people who are going to plant a billion trees and nobody gives us any credit,” Janzen laments. What’s worse, a lot of those corporate tree-planting campaigns are fundamentally flawed.

The first seeds blew in with the wind

“A lot of the reforestation projects are kind of assuming that trees are mechanical objects,” Hallwachs says. But they don’t stand alone, not in a healthy forest.

Merely plant rows of trees, and the result is a tree plantation — not a forest. Bringing back a forest is a much different endeavor. It’s more about restoring relationships — reconnecting remaining forests with land that’s been cleared and nurturing new kinds of connections between people and the land.

In ACG’s dry forest, they didn’t have to plant trees by hand. By getting rid of the grass and stopping the fires, they cleared the way for the forest’s return. The first seeds blew in with the wind.

Hallwachs and Janzen recognize them like old friends — stopping next to a Dalbergia tree that was one of the first to grow where they stomped out the fires. Its seeds are light and flat, allowing them to float on a breeze. When those trees start to grow, they attract animals in search of food or shelter.

Janzen measures each animal up by how many seeds they can hold and then spit or defecate onto the forest floor. “When you see a bird fly by, what you’re seeing is a tablespoon full of seeds,” he says. “Every deer you see is a liter of seeds.”

Now, ACG is estimated to hold as many as 235,000 different terrestrial species — representing around 2.6 percent of global biodiversity. For comparison, Costa Rica as a whole holds roughly 4 percent of the world’s biodiversity, home to more species than the US and Canada combined. The ACG is now a world heritage site spanning not just dry forest but nearby rainforest, cloud forest, and marine ecosystems.

The forest across the field is considered “secondary.” In other words, it’s not the original forest; it’s one that’s grown back after being cleared. Today, more than 75 percent of the country is blanketed by forest, and more than half of that canopy is young secondary forest. It plays a critical role in protecting biodiversity, giving threatened species a home and slowing climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

It’s also where the couple has built a humble home nestled under a secondary canopy. They spend three months at a time here, bouncing back and forth between Guanacaste and Philadelphia, where Janzen is a professor of biology emeritus and Hallwachs is a research biologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

The front porch is a couple of plastic lawn chairs on the forest floor, shaded by corrugated metal. A web of clotheslines hangs from wooden rafters inside, clothespins securing bags of plants and other specimens they’ve collected over the years. Somewhere among the glass jars and more plastic bags on Janzen’s desk, he fishes out a wooden bobbin like those that his wife used to track agoutis’ movements by following threads along the forest floor. Now, there’s an agouti foraging outside the front door the couple keeps open to the forest.

“There was a time when we thought [agoutis] would never show up at our house because our house was in the pasture. It was so far away from all of this,” Janzen recalls. “Today, they’re there every morning.”

“The living dead”

A short drive from Janzen and Hallwachs’ home, along a stretch of the winding paved road through the ACG, the tree canopy seems to close in overhead. With the windows rolled down, you can smell the shift to musty, moist earth. Stop and step outside, and the forest floor is darker, spongier. The thick foliage above filters out more sunlight; more of those leaves have accumulated and decayed on the ground for centuries without burning. In other parts of the park, Janzen can bring his walking stick down with a thud, hitting harder, more compact soil. Here, his walking stick rustles through layers of leaf litter.

“You’re standing in the only piece of original dry forest between Brownsville, Texas, and the Panama Canal [along] a paved road,” Janzen says.

This 22-hectare sprawl, just half as big as the Mall of America, is a gem in the ACG. It’s the source of seeds that blew into old pastures. In an ideal world — with several more centuries and a stable climate — primary forests like this might have grown to infiltrate the secondary forests it now has as neighbors. In other words, more of the ACG might look and feel like this original forest.

“The intent was always that. Then comes climate change,” Hallwachs says.

While it’s hotter and drier in this part of the world because of climate change, it’s noticeably cooler in the original forest than in areas nearby that have been razed. It’s another benefit of the old evergreen trees towering overhead. Janzen leads us to a 300-year-old tree. The common name for it, he explains, is chicle — the Spanish word for chewing gum, which can be made from the white latex under its bark.

We visit another ancient tree, the guapinol. Amber jewelry is made from its fossil resin. Its seeds are the same ones the agouti bury across the forest. “And that’s how the forest moves,” Janzen says.

But the last time the tree bore fruit was about 25 years ago. For a tree that only flowers every quarter-century, everything needs to be just right for it to successfully reproduce — enough water and nutrients and plenty of pollinators (in the guapinol’s case, bats). If that doesn’t happen, you could lose the next generation. Here in the ACG, the guapinol is one of what Hallwachs and Janzen call “the living dead.”

“The climate for their successful reproduction has already moved on,” Hallwachs says. “So what will be here in 25 years? We are very much hoping there will be forest in 25, 50 years. But there will be some of these classic species that won’t be able to make it.”

This is what gives me hope

The forest is changing faster than Janzen, Hallwachs, and other researchers can document. There’s not much to do about it except to stop climate change and deforestation, they say, and keep on with their work of restoring the landscape. The ACG’s other ecosystems have suffered from climate change, too — from coral reefs losing their color in the heat to cloud forests losing their clouds.

“At this point in time and budgets, ACG does not require more classical academic scientific study of climate change impacts,” they wrote in their 2021 PNAS article. “Confronted with a metaphorical burning house today in the tropics, the critical priority is the complex of fire departments, fire codes, fire alarms, fire exits, emergency rooms for burn victims, and rules and views that prohibit candles in Christmas trees, rather than for more and fancier thermometers.”

Scrolling through photos of ACG’s coral reef bleaching last year, Chavarría tells The Verge, “This is really hard for me being here, documenting this. Sometimes I want to cry.” The water was so hot it felt like jumping into soup. Under stress, corals expel the algae that give them their color and energy. If the bleaching lasts too long, the corals could die.

She’s tried to get funding to restore the reef and figure out which corals could be more resilient to climate change but hasn’t had luck yet, she says. Still, she believes they can be saved. “This is what gives me hope,” she says, pointing to a colony of coral that didn’t bleach. It’s still pink. This is what conservationists should pay attention to, she says, her voice still upbeat.

When things get rough, Chavarría heads to a lookout point where she can see the hectares of forest below that she’s helped to revive. It reminds her of what’s possible.

There is still hope and growth in Guanacaste. The ACG team’s restoration efforts are expanding outside of its official borders. Working with local women on a former salt flat, Chavarría is restoring a coastal mangrove forest, which has proven to be even more effective at storing carbon dioxide than other kinds of forests of the same size, keeping the greenhouse gas from further heating the planet. Thick mangrove roots also grip the earth so tightly that they can protect coastlines from rising seas and erosion.

The project is also expected to improve fishing prospects for residents who depend on it for food and livelihood. That kind of community buy-in to the forests’ survival has been one of the pillars of ACG since its inception. Officially, they call it biodesarrollo, or biodevelopment. In practice, it’s relationship-building. Chavarría started a program for kids in a local fishing town, taking them snorkeling to learn more about the ocean ecosystem. She remembers one of the very first kids in the program jumping out of the water, screaming, “María, they are colorful!” Before that moment, she says, “These kids know the fish just fried in the pan, never alive in the reef.” The program got mothers in town curious and, now, more involved in projects like restoring the mangrove forest.

It’s tough work, planting seedlings along newly dug canals while your boots sink into brackish mud. But they won’t have to plant too many trees — just enough to stabilize water canals that bring back the natural ebb and flow of the tide to this former salt flat. Each tide washes away layers of salt, picks up seedlings from surviving mangrove trees nearby, and deposits them here to grow.

Photography by Justine Calma / The Verge

The International Center for Journalists supported this reporting, and Punto y Aparte contributed to the report.