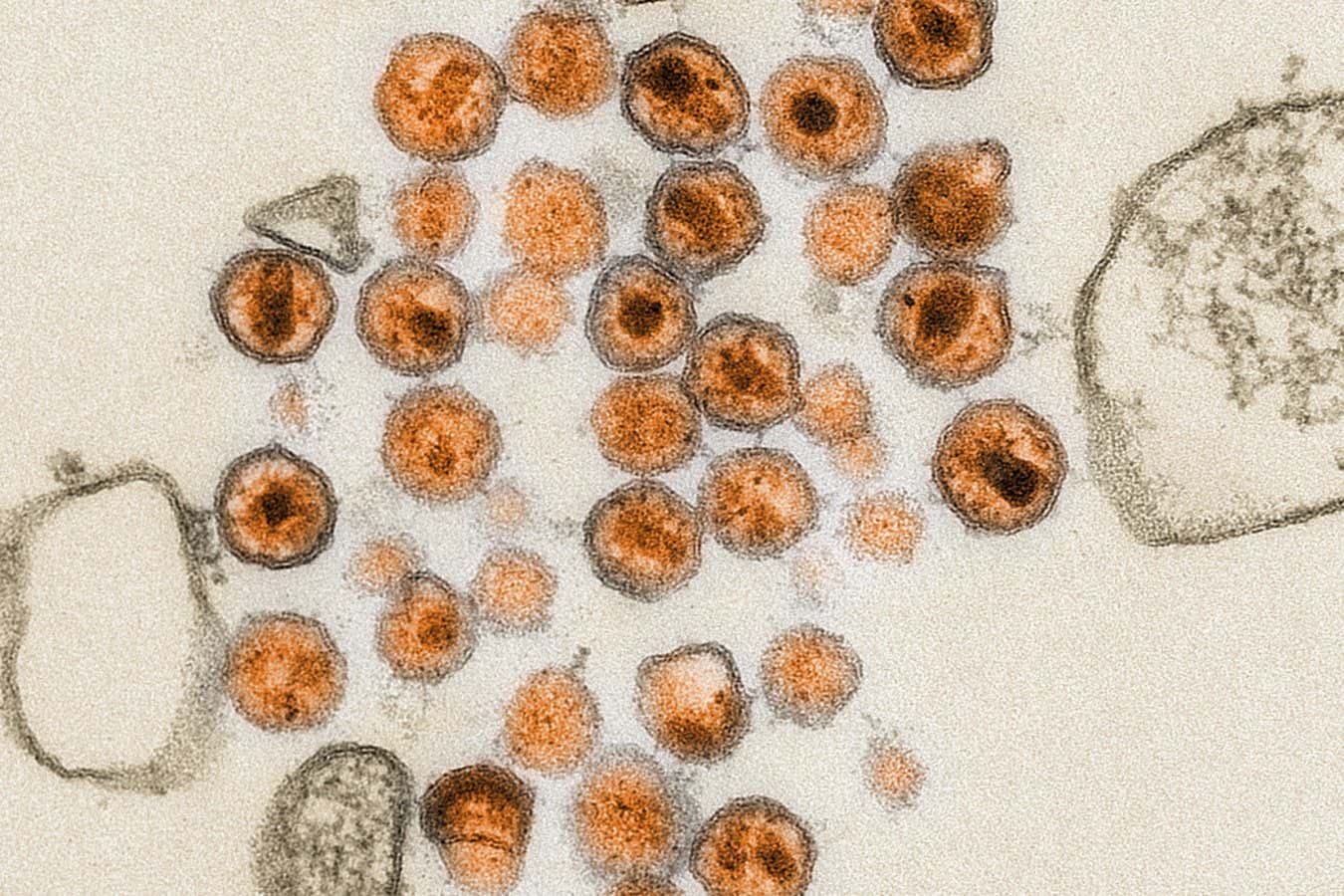

An electron micrograph of HIV, which currently requires lifelong medication

Scott Camazine/Alamy Stock Photo

A new way to eradicate HIV from the body could one day be turned into a cure for infection by this virus, although it hasn’t yet been shown to work in people.

The strategy uses a relatively recent genetic technique called CRISPR, which can make cuts in DNA to introduce errors into viral genetic material within immune cells. “These findings represent a pivotal advancement towards designing a cure strategy,” researcher Elena Herrera Carrillo at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands said in a statement.

While infection with HIV was once nearly always fatal, those with the virus can now take drugs that stop it from reproducing. This gives them a nearly normal lifespan, as long as they diligently take their medicines every day.

But when people are first infected, some of the virus inserts its DNA into their immune cells, where it stays dormant. If they stop taking their HIV medicines, this DNA “reawakens” and the virus starts spreading through their immune systems again.

For a cure, we need some way of killing any dormant virus in the body. Several strategies have been tried, but none has so far been found to work.

The latest approach uses a gene-editing system called CRISPR. Originally discovered in bacteria, this homes in on a specific DNA sequence, making cuts in it. By changing the DNA sequence being targeted, the system can potentially be turned into a form of gene therapy for many conditions, with the first such treatment having been approved last year in the US and UK as a cure for sickle cell anaemia.

Several groups are investigating using CRISPR that targets a gene in HIV as a way of disabling dormant virus. Now, Carrillo and her team have shown that, when tested on immune cells in a dish, their CRISPR system could disable all virus, eliminating it from these cells. The work is due to be presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in Barcelona, Spain, next month.

Jonathan Stoye at the Francis Crick Institute in London says that although the results are encouraging, the next step is trials in animals and eventually people to show the treatment can reach all the immune cells with dormant HIV. Some of these cells are thought to reside in bone marrow, but there may be other body sites involved too, he says. “There’s still a fair amount of uncertainty about whether there are other reservoirs in other parts of the body,” he says.

A Californian firm called Excision BioTherapeutics has previously shown that a CRISPR-based approach can reduce the amount of dormant virus in monkeys infected with a similar virus to HIV.

Topics: