Football arguably doesn’t need anything extra to feed its collective sense of self-importance, but the idea that it can cause new life to be created will certainly do it.

You might remember a rather dramatic game in the National League towards the end of last season when Wrexham and Notts County faced each other in what was effectively a ‘winner takes promotion’ clash. In the 97th minute, Wrexham goalkeeper Ben Foster saved a penalty to seal a 3-2 win, putting them three points clear with a game in hand on their rivals.

According to Foster, the result of the collective ecstasy of that moment was made clear nine months later: he recently recorded a video in which he claimed the birth rate in the Wrexham Maelor Hospital went up by 24 per cent in January 2024 when compared to a year earlier.

That clip was tweeted by Wrexham co-owner Ryan Reynolds, father of four, adding the comment: “Normally this happens when you pull the goalie, not the other way around. Trust me.”

Normally this happens when you pull the goalie, not the other way around. Trust me. pic.twitter.com/fIT0SoVFTY

— Ryan Reynolds (@VancityReynolds) February 14, 2024

This is a titillating theory that crops up now and then, the idea that there is a definitive correlation between a team’s moments of success and a mini baby boom. Probably most famous in football is the ‘Iniesta generation’: the story was that the Barcelona midfielder’s last-minute winning goal against Chelsea in the 2009 Champions League semi-final inspired so many moments of intimacy that, nine months later, the maternity wards of Catalonia were swamped.

“There will be a lot of love made tonight,” said Gerard Pique after that goal, and initial reports suggested the birth rate went up by 45 per cent the following January. In 2020, Iniesta made surprise video calls to a couple of the kids who supposedly resulted from the celebrations, asking one if his mother had shown him the video of the goal. Which is a bit weird: would you like to be saddled with the knowledge of what got your parents in the mood for your conception?

There are plenty of other similar reports. The Boston Red Sox’s 2004 World Series win, their first in 86 years, apparently resulted in a mini baby boom. There were similar stories in New Zealand after the 2011 Rugby World Cup. There has also been a long-running theory that birth rates would go up in the cities of teams that won the Super Bowl, encouraged by a commercial produced by the NFL in 2016 that cited no less a source than “data” to prove the theory.

But is any of this true? Do sporting successes double as aphrodisiacs, and subsequently result in many additions to the population?

The short answer to the question is… no. Or at least… probably not.

Let’s start with the Foster-Wrexham example: to begin with, it is slightly difficult to establish the accuracy of the figure that Foster cites. It is credited to the Maelor Hospital, but The Athletic contacted the NHS health board that manages that hospital, which reported nothing out of the ordinary about the birth rates in January, compared to recent months or indeed the same point of the previous year. That health board (which encompasses other hospitals, in addition to Maelor) said its birth rates across the region in January 2024 had gone up in comparison to a year earlier, but only by 1.5 per cent.

Foster’s representatives couldn’t help, neither could Wrexham. Further rats are potentially smelled by the origin of Foster’s video: it was part of a Valentine’s Day promotion with one of his sponsors, pushing a line of baby announcement-related products. That company couldn’t clarify where the statistic came from either.

But hey, one exaggerated commercial stunt doesn’t necessarily disprove the theory. What about the Iniesta generation?

For starters, that figure of 45 per cent is nonsense, the result of a statement from the spokesperson from one hospital, the Quiron in Barcelona, which said births were up from nine or 10 a day to 14 or 15. It’s the sort of sample size that will bring most statisticians out in a rash.

Still, a broader and more scientific study from 2013, published in the British Medical Journal, did suggest there was an increase. The study looked at birth rates in two central Catalan counties — Solsones and Bages — over 60 months from 2007 to 2011.

The study read: “Our results show a transitory and significant 16 per cent increase in births in February 2010, nine months after FC Barcelona’s exciting victories in May 2009 — far short of the 45 per cent increase reported by the media. We may infer that — at least among the target population — the heightened euphoria following a victory can cultivate hedonic sensations that result in intimate celebrations, of which unplanned births may be a consequence.”

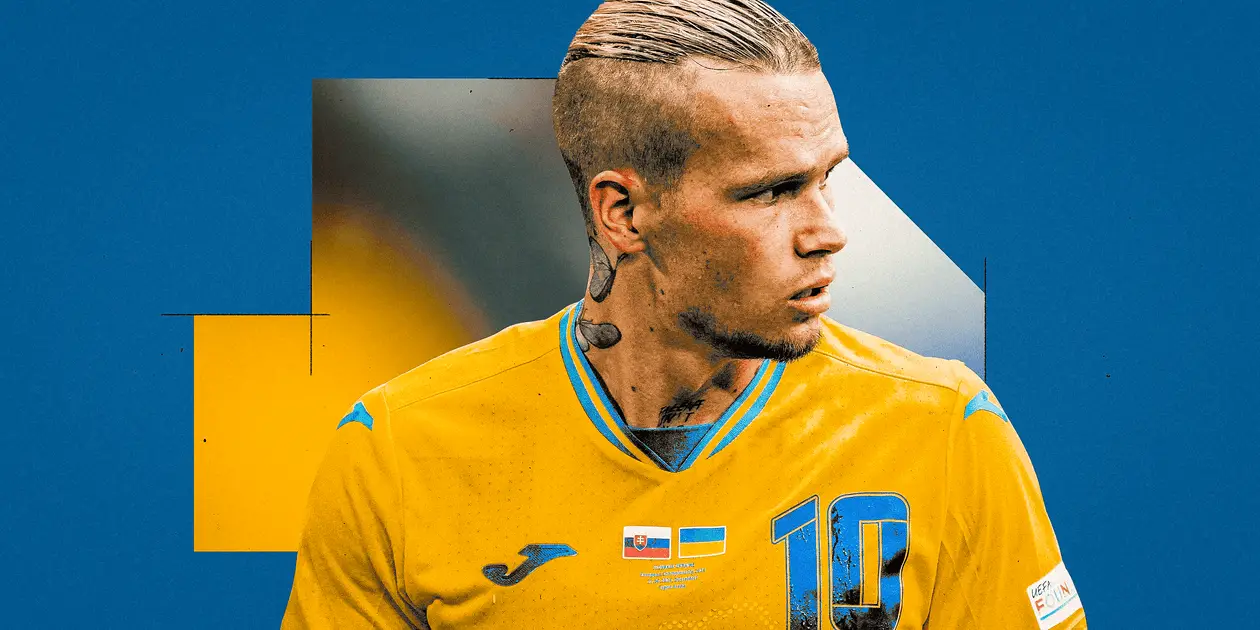

Foster makes the crucial save last year (Simon Stacpoole/Offside/Offside via Getty Images)

If, at this stage, you need to take a moment to fan yourself down having been overcome with amour at this saucy language, then please do.

The trouble is that, short of tracking down everyone who gave birth in those regions in February 2010 and asking if it was Iniesta’s goal that got them so excited, there’s no real way of proving a definitive link. Even the authors of the report were divided on that point, and they admitted their allegiances may have influenced their conclusions.

The reports stated that “some of the authors (who happen to be Barca supporters) believe that an intense and brief stimulus (the Barca triumphs in May 2009) was the cause of the increase in births. The remaining authors (who, incidentally, are not Barca supporters) interpret that the term ‘Iniesta generation’ is a misnomer”. Big club bias… it even gets academic researchers.

What about World Cup victories? If this theory were true, should they not inspire nationwide copulation and subsequent logjams in maternity wards everywhere? Well, maybe. A look at the birth rates in Spain after they won the 2010 World Cup in South Africa does suggest something might be afoot. According to statistics from the Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, March 2011 (ie, nine months after Iniesta’s extra-time winner for Spain) saw 40,036 births, as opposed to 38,621 in January, 36,694 in February, 37,528 in April and 39,462 in May.

Iniesta’s 2010 #WorldCup final goal changed Spanish football forever!🇪🇸👏🏆

📺https://t.co/ezhfwgVNdI pic.twitter.com/DMSzUDF6iZ

— FIFA World Cup (@FIFAWorldCup) May 8, 2018

Aha! A definite increase, then. But a look at figures from previous years shows there were 41,830 births in March 2009 and 40,462 in March 2010. Ah. Not so much, then.

Furthermore, researchers from the Institute of Labor Economics in Germany produced a study in 2021 that looked at monthly birth rates in 50 countries going back to 1965, and correlated them with World Cups and European Championships, and actually found birth rates went down nine months after those tournaments, not up.

“According to the authors,” the report said, “a possible explanation might be that a massive increase in the consumption of media and entertainment, followed by extensive celebrations with friends and compatriots, comes at the expense of ‘intimacy time’.”

There has seemingly been quite a large amount of academic research into this phenomenon. One, by Fabrizio Bernardi and Marco Cozzani for the European Journal of Population, really went deep into the weeds, plotting birth data from Spain between 2001 and 2015 against betting odds, to look at “mood shocks arising” from results. They found very little correlation, but the study was worth reading if only for the subheading of “Celebratory intercourse versus sorrowful abstention”.

The Super Bowl theory was mentioned earlier but, as it turns out, that’s probably nonsense too. Another study, conducted by academics from the University of North Carolina, found that there were basically no changes in the birth rates in Super Bowl-winning cities nine months after the big game.

In the few instances that there were any changes, the report found that, like with the study related to World Cups and European Championships, they decreased, rather than increased.

All of which isn’t a particular surprise to Josh Wilde, a fertility researcher for the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science at Oxford University.

“There are never really things you can point to, huge euphoric effects,” he says when asked what sort of thing tends to cause spikes in birth rates, pointing out that single identifiable events (like Covid-19 or financial problems in a country) are more likely to be behind decreases than increases. “The greatest predictor in short-term changes in birth rates is the unemployment rate — by far.”

Wilde explains that you can always find examples of increases in birth rates, which it is then possible to trace back to a sporting victory of some description. But first, these tend to be cherry-picked and highlighted by people using it to perhaps promote a product or create an eye-catching headline, and second, it’s basically impossible to prove whether they are linked to that sporting victory.

“Can they?” he says when asked if sporting events can cause a birth rate spike. “Well, anything is possible. But do they? No.

“The other thing you have to consider is that accidental births happen, but they’re becoming more and more rare. If you have a couple that has sex once a week, and then they decide to have sex twice a week, they’re not going to double the number of kids they have, because they’re on contraception or organise their lives in some way to prevent those births.

“If you’re one of those couples and you suddenly get happy because your team won, that might cause a few accidental births, but not enough to be detectable at the population level.”

Wilde also points out that this isn’t generally how people express their delight about their team winning a big game. As a rule, people might celebrate by going out drinking, or by driving through the streets beeping the horns of their cars and twirling a scarf around their heads, but probably not by heading to the bedroom.

Feel free to contradict this in the comments, but you would imagine that very few fans return home with a bottle of champagne in their hand and a rose between their teeth, declaring to their beloved: “Darling: victory! Follow me upstairs!” It’s a relatively offensive notion, if nothing else: you probably wouldn’t feel great if the reason that your partner wishes to get intimate is because their passions have been stirred not by you, but by a sporting event.

Wilde says: “Think about people who aren’t on contraception and would be prone to these accidental births: what fraction of them are going to be so happy about a World Cup win, that they are even in that situation? It’s a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of people who are even in the situation where this could happen, and so if you get some claim that says birth rates increase by 40 per cent, it’s laughably implausible.

“Will you find online some cherry-picked examples of birth rates that go up nine months after sporting events? You will. Is that a systematic thing that happens in the real world? No.”

So there we have it. It is our solemn duty to report to Ben Foster that, alas, he almost certainly was not responsible for a large number of new babies in the Wrexham area. And it would appear that football — or any sport, really — can’t take the credit for an upsurge in new life.

Ultimately, it’s probably for the best.