The UK may be experiencing its biggest outbreak of whooping cough in two decades, with five deaths reported among infants who developed the disease in England between January and March.

According to the latest data published by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) on Thursday, cases of whooping cough continue to increase, with 1,319 confirmed in March. This brings the total number of confirmed cases during the first quarter of 2024 to 2,793. The true number of cases is likely to be much higher though, because mild cases are easily confused with other respiratory illnesses in the early stages when the infection can be tested for.

Just over half of the cases (51%) were in people of 15 years or older who usually experience a mild, yet unpleasant illness, characterised by violent coughing fits interspersed with a loud, high-pitched “whooping” sound as they try to draw breath.

However, rates of whooping cough remain highest in babies under three months of age, who may not cough at all, but instead turn blue or struggle to breathe. They are at greatest risk of severe complications or death.

Dr Gayatri Amirthalingam, a consultant epidemiologist at the UKHSA, said: “What we are currently seeing is very high case numbers, certainly higher than the 2016 peak, based on the projections so far in the first three months, and very much in line – and potentially even higher – than what we saw during our 2012 peak year, particularly in very young babies.

“Although it is difficult to make predictions, we do see waves [of whooping cough] every three to four years, and these waves can last for several months, so it’s not going to be entirely unexpected if cases continue to rise or at least remain at heightened levels for several months.

“It is certainly a real concern, which is why we are trying to raise awareness – particularly among pregnant women and the parents of young children – that whooping cough is on the rise and it is really important that they take the opportunity to get vaccinated.”

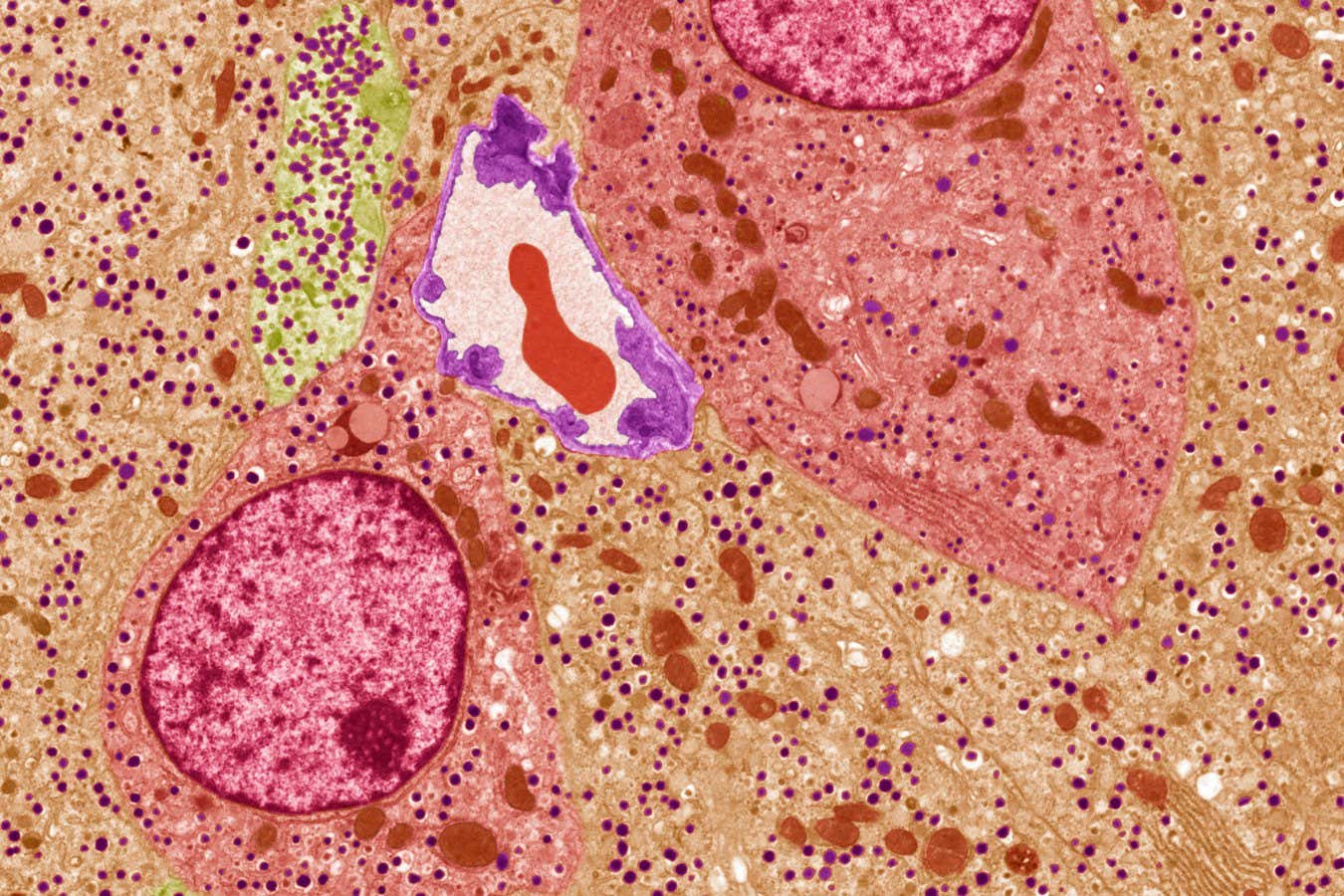

Whooping cough – or pertussis – is caused by a bacterium that is transmitted by coughing, sneezing or sharing the same breathing space as an infected person. Early indications include mild, cold-like symptoms, a low fever and occasional coughing. These usually last for one to two weeks, after which the coughing fits begin.

These tend to be more common at night, and may be so severe that they cause retching, vomiting or fractured ribs. They can continue for up to 10 weeks, after which they gradually diminish. Whooping cough is also known as the 100-day cough.

Antibiotics can reduce the severity of the infection and prevent it from spreading to others, but need to be started in the first three weeks of illness – ideally before the coughing fits begin – when the bacteria are still in the body.

Vaccination remains the best defence. In the UK, this is given through a “six-in-one” combined jab at eight, 12 and 16 weeks of age, which also protects against other diseases such as tetanus and polio, followed by a pre-school booster at age three.

While whooping cough vaccines are highly effective at preventing severe disease and complications, the protection is not lifelong. One recent Canadian study found that vaccines provided 80-84% protection against infection during the first four years, but immunity started to wane beyond this.

A maternal whooping cough vaccination programme has been running since 2012, which aims to protect newborns, who are too young to be vaccinated, and provides 92% protection against infant death. It was introduced in 2012 after the last main wave of whooping cough that resulted in 9,367 confirmed cases in England, and 14 deaths – all in babies too young to be fully protected by infant vaccination.

after newsletter promotion

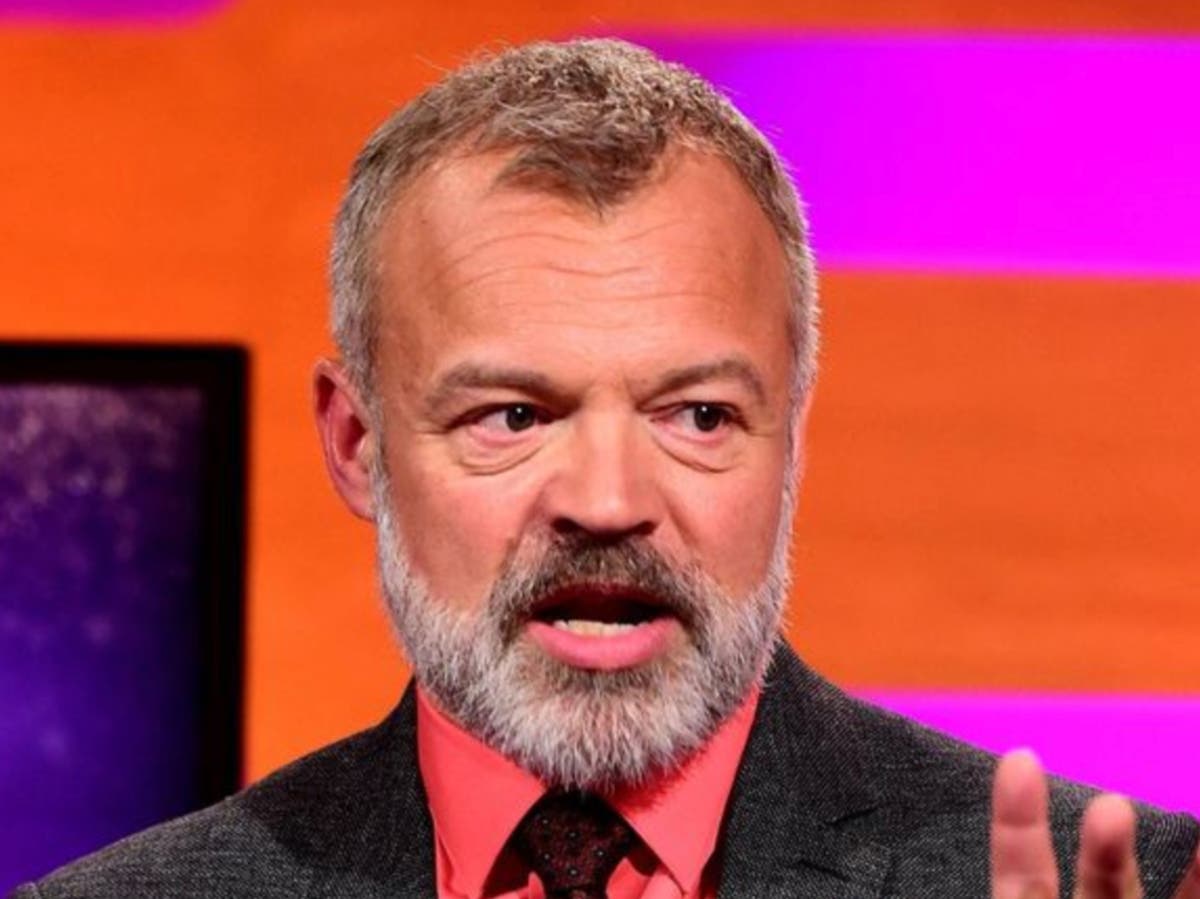

According to Dr Elizabeth Whittaker, a senior clinical lecturer in paediatric infectious diseases and immunology at Imperial College London, there are several reasons for the current outbreak.

One is that uptake of maternal vaccines has fallen in recent years to an average of 59% in late 2023, with rates as low as 30% in north-east London. Another is that rates of exposure to the bacterium during the Covid crisis were extremely low, because of measures brought in to prevent transmission of Covid, resulting in a larger number of people who are susceptible to catching and transmitting the infection.

Covid also meant that some children missed out on their preschool booster, which is important for maintaining their immunity. “Where I work in London, Hammersmith and Fulham, only 62% of children have had a preschool booster, which means you’ve got a really low level of protection,” said Whittaker.

“We’re basically in the perfect storm of adults who have waned immunity because they had the vaccine when they were children; a lot of primary school-aged children who are missing the booster dose, so it is transmitting freely in adults and in primary schools; and then we don’t have [as much of] the protective vaccine in pregnant women, so if their babies are exposed, they’re more likely to end up with severe disease.

“On top of that, it is normal for us to see a pertussis wave every two to three years, but we missed that because of the pandemic, so this is a delayed wave. And this means that it’s going to be big, because there’s more vulnerable people altogether.”