Lars Fruergaard Jorgensen has a problem: Too many people want what he’s selling.

Mr. Jorgensen is the chief executive of Novo Nordisk, the Danish drugmaker. Even if the company isn’t quite a household name, the TV jingle for its best-selling drug — “Oh-oh-ohhh, Ozempic!” — might ring in your ears. Across the United States, Novo Nordisk’s diabetes and weight-loss drugs, Ozempic and Wegovy, have soared to celebrity status and helped make the company Europe’s most valuable public firm. It can’t make enough of the drugs.

Mr. Jorgensen’s problem is one many top executives wouldn’t mind, but the success caught him off guard. Last year, when the company was celebrating its centenary, Novo Nordisk’s revenue jumped by a third, to 232 billion Danish kroner, or $33 billion.

“Nobody had forecast this growth — no analyst, nobody in the company,” Mr. Jorgensen said in a recent interview at the company’s headquarters in a suburb of Copenhagen. “Nobody forecast a 100-year-old company would grow more than 30 percent,” he said, seemingly torn between pride and amazement.

For most of its 100 years Novo Nordisk has been focused on the steady business of treating diabetes, one of the world’s most prevalent chronic diseases. Even today, it produces half the world’s insulin. But the development of Ozempic and Wegovy has led to a bigger and bolder ambition to “defeat serious chronic diseases.” That includes treating, and even preventing, obesity, which is linked to other health issues like heart and kidney diseases.

By pursuing a much larger target than diabetes, the company expects to unlock the door to a multibillion-dollar market with nearly a billion potential patients. In the United States alone, more than 40 percent of adults are obese.

And so the Danish drugmaker is undergoing vast changes — it’s getting bigger, more international and closer to the heat of the spotlight. Mr. Jorgensen is trying to ramp up production to meet the huge demand for its weight-loss drugs, stay ahead of competition from Eli Lilly and others and ensure the company’s future so it can meet its lofty goal.

But in all the tumult, there is something executives are trying to hold on to: the company’s longstanding values, codified in the “Novo Nordisk Way.”

Those principles, which include having a “patient-centered business approach,” have helped earn the company a good reputation at home, where it’s considered a place where people are proud to work. But these guideposts are facing pressure as tens of thousands of new employees are hired, lawmakers denounce the drugmaker for its high prices and counterfeit versions of its products make people sick.

#Ozempic

The drugmaker’s head office is a homage to its roots: a modern six-story white circular building inspired by the molecular structure of insulin. A staircase spirals around an open atrium. On the top floor, Mr. Jorgensen and the executive team share an open-plan office space.

“Many of us have been here forever,” Mr. Jorgensen, 57, said as a snowstorm gathered strength outside.

He’s worked at Novo Nordisk for more than three decades, and became chief executive in 2017, a turbulent period when the insulin market was under strain: “Three profit warnings in one year, and the share price had tanked by 40 percent,” he recalled.

About a year later, Ozempic hit the market.

Now Novo Nordisk consistently beats investor expectations. Last summer, it eclipsed the French luxury group LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton to become Europe’s most valuable company. Its market value exceeds $555 billion.

For those on the sixth floor, who rose through the ranks of a company that concentrated on insulin, the changes are coming quickly.

“Now it’s new patients; a new product presentation; sometimes new molecules,” Mr. Jorgensen said. “It’s a completely different, say, management system and supply chain that’s required.”

The heart of the growth is semaglutide, Novo Nordisk’s synthetic version of a hormone known as glucagon-like peptide 1, or GLP-1, which helps the body regulate blood sugar levels. The patent developed by the company also proved remarkably effective for weight loss. It causes people to feel fuller when they eat and reduces cravings. Physicians say it could revolutionize the way we think about obesity and what we eat; food executives fear the same thing.

Semaglutide revived the fortunes of Novo Nordisk. A couple of decades ago, the company was falling behind international peers, with failed insulin medical trials and too little innovation. And then insulin started drying up as a source of profits, as U.S. lawmakers pushed price caps and drugmakers were forced to pay larger rebates.

Ozempic, the brand name for semaglutide, a weekly injection for Type 2 diabetes patients, has been around for more than six years. But in the last couple of years, there was an explosion in popularity, helped along by heavy advertising, social media videos and intrigue over celebrity use. Elon Musk said he used it, and at the Oscars last year Jimmy Kimmel made a gag about it. TikTok videos tagged Ozempic have more than one billion views, with people documenting their weight loss.

As Ozempic began to take off, Novo Nordisk pushed ahead with Wegovy, which is semaglutide marketed specifically for weight loss. By the time it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in mid-2021, the Danish company knew it had “something special,” said Camilla Sylvest, the executive vice president for commercial strategy and corporate affairs.

Novo Nordisk leads the pack in obesity treatment, but it now has strong competition from Eli Lilly, which sells a similar drug under the brand names Mounjaro, for diabetes, and Zepbound, for weight loss. Other pharmaceutical companies are clambering to catch up.

By far, most people using Ozempic (two thirds of its sales last year) and Wegovy (nearly all of its sales) are in the United States. That’s partly because drugs tend to be introduced first in the United States.

That means the Danes essentially have Americans to thank for their economic growth. The expansion of the pharmaceutical industry, mostly due to Novo Nordisk, was responsible for all of Denmark’s economic growth last year.

High Prices, Loud Criticism

The cost of these drugs, though, has made Novo Nordisk a target.

“There is no rational reason, other than greed, for Novo Nordisk to charge Americans nearly $1,000 a month for Ozempic,” Senator Bernie Sanders, independent of Vermont, said last month. A frequent critic of high drug prices, he said Canadians paid $155 a month and Germans just $59.

Ozempic could be a “game changer” fighting diabetes and obesity, Mr. Sanders added, but “this outrageously high price has the potential to bankrupt Medicare, the American people and our entire health care system.”

While the U.S. list price for Ozempic is a little under $1,000 a month and about $1,350 for Wegovy, Novo Nordisk says most American patients pay $25 or less for Wegovy. Much of the rest of the cost is shouldered by insurance plans, and some have been overwhelmed. This month, facing ballooning costs, North Carolina quit providing insurance coverage for obesity drugs for state employees. Even Denmark’s national health service won’t subsidize Wegovy, arguing that it isn’t cost effective.

Mr. Jorgensen argues that high rates of obesity lead to enormous medical costs, and that drugs to end obesity ultimately save money. “Health care systems are challenged, with aging populations,” he said. “They’re going to break unless we do something about obesity.”

The Novo Nordisk Way

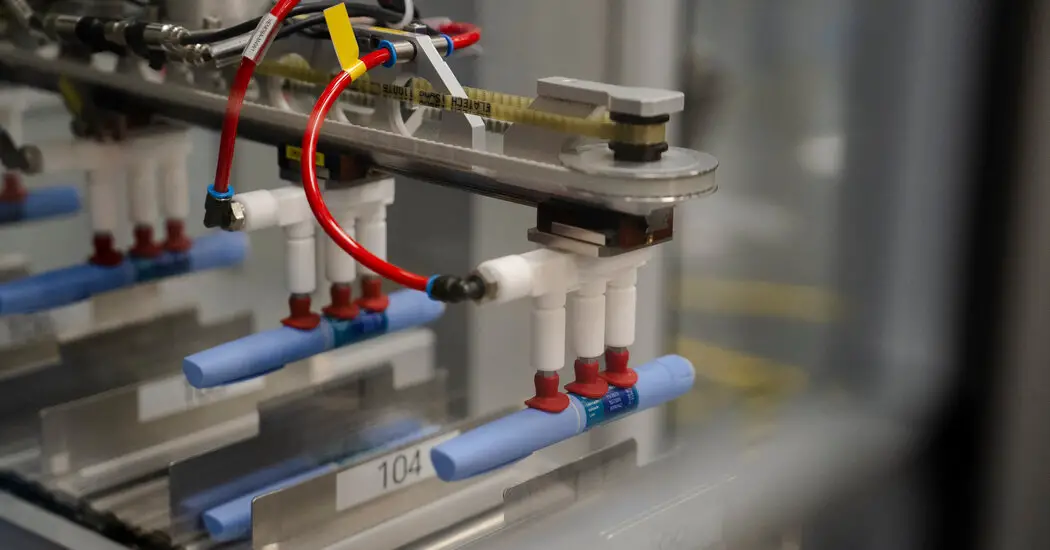

Although the company’s production facilities operate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, the limited supply of Ozempic and Wegovy is expected to last for several more years, worrying diabetics while counterfeits are leaking into the market.

Production capacity is a recurring headache. Novo Nordisk has more than 64,000 employees, and traffic jams outside its buildings are common. At the headquarters in Bagsvaerd, arrivals after 9 a.m. might struggle to find a desk.

So Novo Nordisk is in the middle of remaking itself. Cranes and construction workers have descended on its sites as it spends more than $6 billion this year to expand manufacturing, nearly four times the amount it spent just two years ago. The company is buying more production sites and vacuuming up office space in Denmark.

More than 10,000 people were hired last year globally, and the company is becoming more international — specifically American — as it expands research offices in Cambridge, Mass., and buys smaller biotech companies.

Mr. Jorgensen is also trying to transform the mind-set within the company. A couple of years ago, he gathered executives on a retreat for training called NNX, for Novo Nordisk Unknown. The essential question, he said: “What are your own self-limiting beliefs that could trigger you, block you, in actually daring to lead in a different environment?”

Since then, more than 400 managers have been through this program, intended to help them keep up with the company’s sudden growth.

Until drug supplies can better match demand, the company says, it needs to make difficult choices about how to determine who gets what’s available.

Ms. Sylvest says here she is guided by the Novo Nordisk Way, introduced in the late 1990s. It includes 10 principles, like “we are curious and innovate for the benefit of patients and society at large” and “we build and maintain good relations with our stakeholders.”

“One way or the other,” she said, “it always helps us to have these essentials about what’s the right thing to do.”

Novo Nordisk, she added, doesn’t want to just sell where prices are highest — the United States — but expand access internationally for low-income people or those with insufficient insurance, while also keeping existing patients at the top of the list.

Hundreds of Millions of Potential Patients

Until recently, obesity drugs had a dire history, including when Fen-Phen had to be pulled off shelves in the late 1990s for causing serious heart problems.

Obesity was “a therapeutic graveyard,” said Emily Field, a pharmaceuticals analyst at Barclays in London. The drugs either worked well and had bad side effects or led to only middling weight loss, she said.

But the science has changed rapidly, along with public opinion on obesity, which is increasingly understood to be a disease that can be medically treated, rather than a failure of willpower and poor diet.

Novo Nordisk is responsible for some of this changing outlook. Last summer, a five-year study it financed showed that its drugs could reduce the risk of heart attacks, stroke and cardiovascular disease. This is “what really got Novo Nordisk on the radar,” Ms. Field said.

That makes hundreds of millions of people potential patients. The market for obesity medications could grow to $100 billion in the next decade, according to Barclays. So far, Novo Nordisk is treating about 40 million people globally with its diabetes and weight-loss treatments.

The End of Obesity?

The U.S. patents on Ozempic and Wegovy don’t expire until 2032, but already Novo Nordisk is working on new treatments. It’s in advanced development of CagriSema, a weekly injection that is expected to be more effective than Wegovy for shedding weight. Last month, its stock price spiked after early trial results for an oral tablet of another weight-loss treatment.

As the company digs deeper into obesity, which is defined as having a body mass index above 30, the next question is whether the Danish drugmaker can prevent obesity. Can it predict who is at risk, based on genetics and the data, and treat them first?

Last year, Novo Nordisk established the Transformational Prevention Unit, an internal team looking for ways to predict and prevent obesity.

Not everyone is buying the hype. For more than four years, Jefferies has had a negative “underperform” rating on Novo Nordisk stock. Peter Welford, an analyst at the bank in London, thinks obesity drugs will become common and interchangeable, suffering the same fate as insulin, with higher volumes and pressure on net prices.

“Ultimately, we think Novo Nordisk needs to diversify,” Mr. Welford said. But the bank’s bet that Novo Nordisk’s share price is too high hasn’t worked out so far.

“Clearly we’ve been wrong,” he said.