IF I never thought about dementia before, I thought of little else after the condition manifested in my mother. The odd thing was that dementia – Alzheimer’s disease, in her case – didn’t occur to me until she asked, out of the blue, when we had first met.

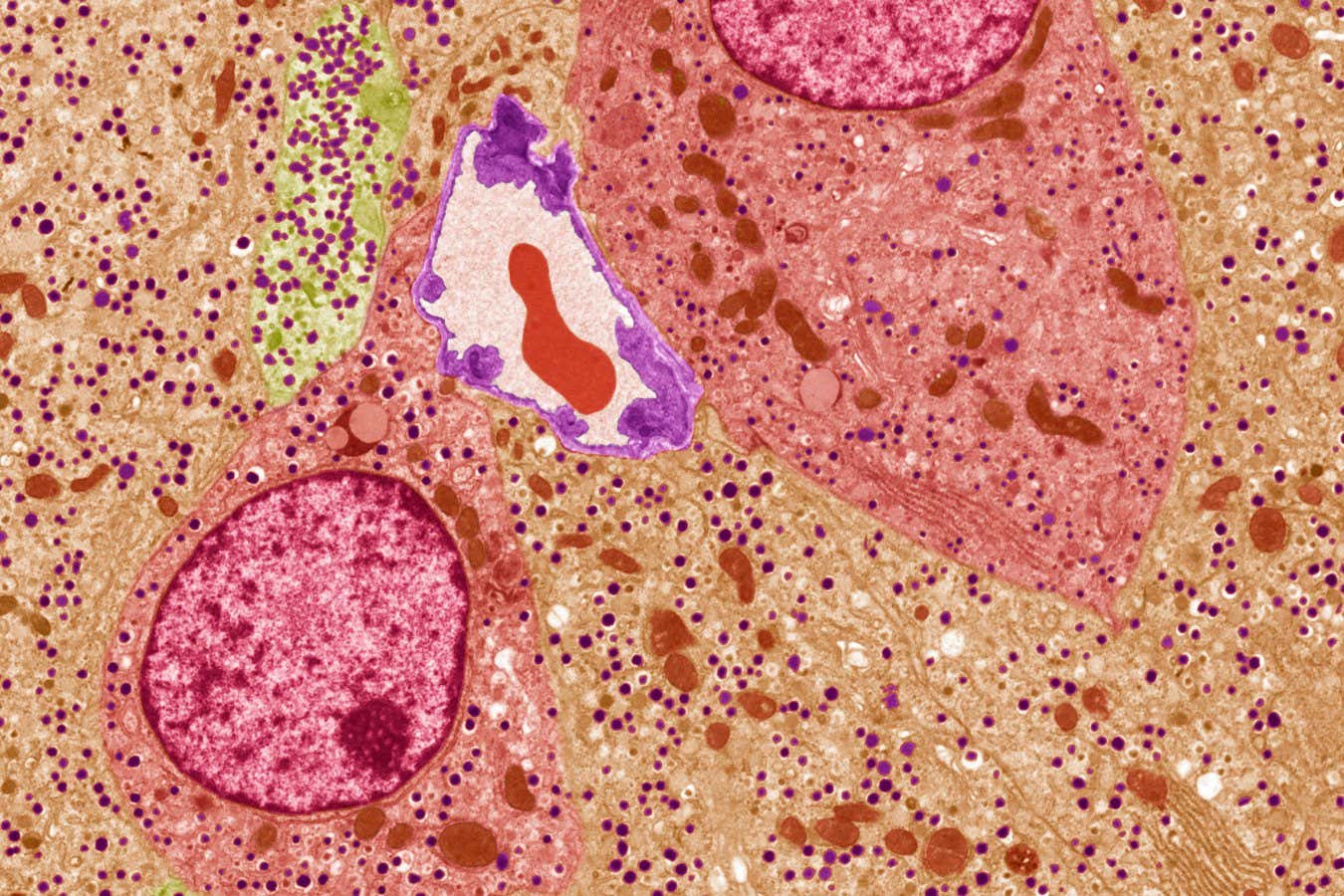

My failure to recognise the extent of her cognitive decline was born partly of denial, but also because she was doubtless compensating for her galloping brain damage, taking cerebral detours around the potholes dug by her condition. After all, she had done this before. Following a stroke four years previously, she had lost the ability to read; after much hard work, she learned the skill again.

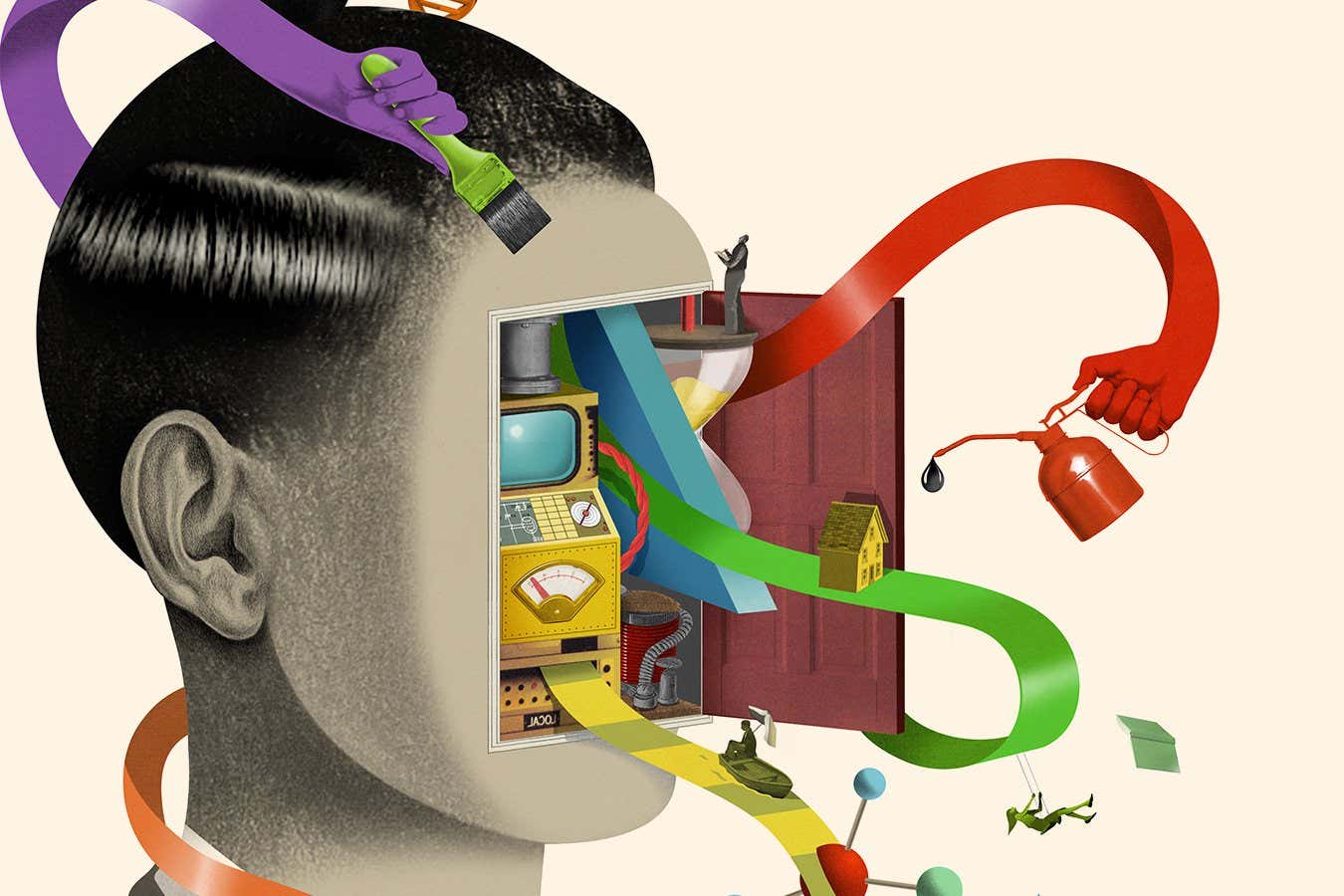

So how come this ability to adapt, which seemed to sustain her after her stroke, was unable to withstand the pathology of dementia? This also made me think about my own resilience to cognitive decline and what, if anything, I could do about it.

We have known for almost three decades that some peoples’ brains can function normally even when riddled with the plaques and other damage associated with dementia, due to an enigmatic capacity called cognitive reserve. Yet despite growing evidence of its importance, it has been challenging to pin down how this quality operates in the brain. Now, we are finally beginning to understand the mechanisms that underlie cognitive reserve, opening up possible new dementia treatments and fresh ideas about how we can protect our thinking abilities into old age. And it turns out that obsessing about learning another language or doing a daily crossword might be missing the bigger picture.

What is cognitive reserve?

The…