NEW YORK — Craig Anderson pauses the phone call. He’s got to get his notes.

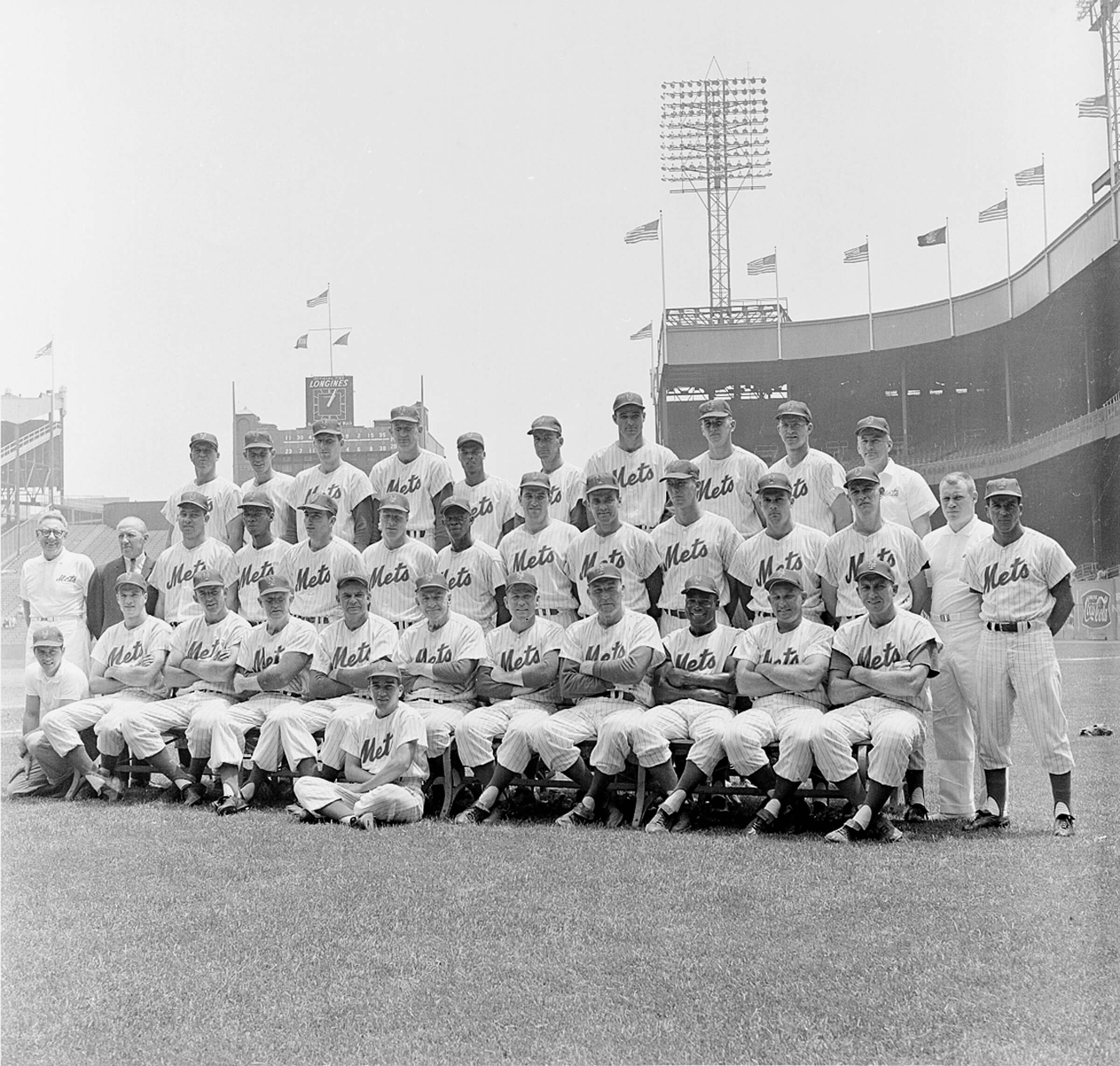

He returns with a sheet of paper he’s had for 62 years — the day-by-day performance of the 1962 New York Mets.

“Somebody gave this to me at the end of the ’62 season,” he says. “I’ve kept it all these years.”

The ledger documents the misfortunes of the losingest team in baseball history — a team on the cusp of one more loss: its place in history.

While nine members of ’62 are still alive, Anderson and fellow pitcher Jay Hook are the only two who spent the entire season with the big-league club. Few people know the burden of history, the burden of ignominious history, like Anderson. The high point of the rookie reliever’s season came May 12, when he earned the win in both games of a doubleheader sweep.

Those would be the last wins he’d ever record in the major leagues, and he set a record by dropping his next 19 decisions. It stood for 29 years, until another Met, Anthony Young, broke it in 1993.

“I didn’t want him to break my record. I didn’t want to wish it on him or anyone,” Anderson says. “That’s the way I felt then and that’s the way I feel now.”

On the phone now, he is matching up the current date — “the Mets started a 13-game losing streak right now,” he notes — while comparing it to the current record for the White Sox.

“I don’t want them to break it,” he says. “I want them to win at least 12 more games. I hope they do, for their sake.”

The Mets visit the south side of Chicago this weekend in the midst of a playoff chase. The White Sox enter the series chasing something grander: history.

The 1962 Mets set the modern-era record for losses in a season with 120. With an even month left in the season, Chicago has lost 104 games, three losses ahead even of the ’62 Mets’ pace for the season. It is easily the most sustained challenge to that team’s record since the 2003 Detroit Tigers needed five wins in their last six games to avoid it.

The White Sox need to go 12-15 to avoid tying the record. They haven’t done that over a 27-game stretch since May. At the moment, they’ve lost 37 of their past 41 contests.

There are not many players who can relate to what that kind of season feels like. Anderson and Hook are two of them.

“It’s shattering when it’s happening to you,” Hook said, his matter-of-fact tone over the phone belying that choice of adjective, “and I’m sure the White Sox are feeling that right now. I wouldn’t wish that on anybody. You don’t like to go through life thinking you were part of the worst team of whatever you did.”

To understand the ’62 Mets, you have to understand Marv Throneberry. Excuse me, Marvelous Marv Throneberry.

The Mets acquired Throneberry, a 28-year-old first baseman, from the Orioles in early May for a player to be named later. (A month later, that player was named as Hobie Landrith, who’d been New York’s first selection in the expansion draft. Landrith had played for the Mets between the trade and the announcement, meaning the two players traded for one another played together for a month.)

Throneberry acquired his ironic moniker with a penchant for misadventure. He mucked up rundowns. He faceplanted racing for the bag. He missed first base — and maybe second, too, the story goes — on a triple. He won a boat he didn’t want in a season-long contest — not much use for a boat in southwest Tennessee, he said — and had to declare it on his taxes.

“Things just sort of keep on happening to me,” he said at one point.

“Marvelous Marv does more than just play first base for the Mets,” wrote Jimmy Breslin in “Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?: The Improbable Saga of the New York Mets’ First Year.” “He is the Mets.”

Marv Throneberry made 17 errors in 97 games at first base for the Mets in 1962. (Associated Press)

Throneberry, who retained his sense of humor throughout that disastrous season, serves as the stand-in for the Mets’ status as lovable losers. They balked in runs. They misplayed fly balls. They allowed nearly one unearned run per game — to go along with more than five earned runs per contest. On average, their games took 15 minutes longer than everyone else’s, which caused one to be declared a tie because it went past curfew. (“Curfew” here was dictated by the Mets’ flight back to New York from Houston.)

Thing is, Anderson and Hook thought the team could be pretty good. A year earlier, the expansion Angels had won 70 games, and the Mets had brought in some big names — Gil Hodges and Roger Craig in the expansion draft, Richie Ashburn in a deal with the Cubs.

“I looked at the roster and thought, ‘Man, that’s a pretty dynamic list,’” said Hook, who was drafted away from the reigning pennant-winner in Cincinnati. “Casey Stengel is the manager and he’d had great success. I really looked at it optimistically. I thought we could be a decent team.”

“I thought we were going to at least be competitive,” Anderson said.

The nine-game losing streak to start the season quelled that optimism. When a 9-3 mark over two weeks in May threatened to restore it, the Mets responded by losing those 17 in a row.

“That was where I started to think that maybe we had some problems,” said Anderson.

One player after the season told Breslin, “Forty games is about all we could win. After all, we were playing against teams that had all major leaguers on them.”

The Mets were still beloved. They drew nearly a million fans to the Polo Grounds, finishing in the middle of the league in attendance — more than Red Sox and Phillies teams around .500.

“The New York fans are true baseball fans,” Anderson said. “I won’t say they forgave us, but they never gave up on us.”

“You see,” Breslin wrote of the city’s affection for the team, “the Mets are losers, just like nearly everybody else in life. This is a team for the cab driver who gets held up and the guy who loses out on a promotion because he didn’t maneuver himself to lunch with the boss enough. It is the team for every guy who has to get out of bed in the morning and go to work for short money on a job he does not like. And it is the team for every woman who looks up ten years later and sees her husband eating dinner in a T-shirt and wonders how the hell she ever let this guy talk her into getting married. The Yankees? Who does well enough to root for them, Laurance Rockefeller?”

It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that a certain feeling gets expressed a lot by those invested in the Mets’ history.

The 2024 White Sox are not worthy of breaking the Mets’ record.

The Mets had no choice but to be bad. Stricter rules in the expansion draft — because the AL’s expansion teams had done better in 1961 — left New York with little to choose from. The amateur draft wasn’t around yet, let alone free agency. The Mets had to build through scouting and trading. The White Sox, on the other hand, are three years removed from consecutive playoff appearances that were supposed to herald a stretch of sustained contention. It’s all collapsed since.

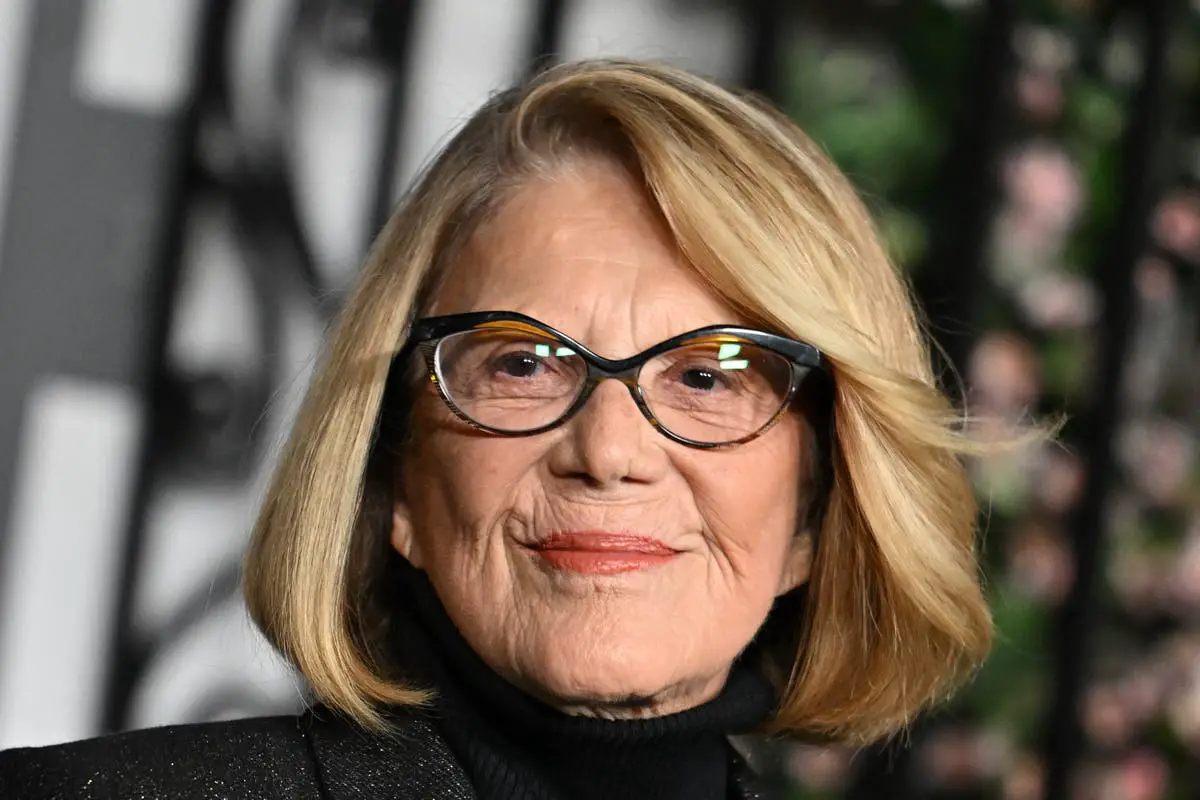

Evan Roberts is the drivetime cohost for WFAN and author of “My Mets Bible: Scoring 30 Years of Baseball Fandom.”

“It’s not life and death, BUT I’d prefer they not break it,” he said via direct message. “I grew up with legendary stories about how bad and hilarious the 1962 Mets were, and I would ideally not want to see a team pass the 120 losses.”

Devin Gordon is the author of “So Many Ways to Lose: The Amazing True Story of the New York Mets — the Best Worst Team in Sports.”

“I suppose I should feel like it’s some kind of albatross around the franchise’s neck and that I should be relieved at the prospect of it finally getting lifted. But I don’t,” he wrote in an email. “That team was a storybook team in its own unique way, and I like that it’s enshrined in history. It’s also the perfect narrative bookend for what happened seven years later with the World Series win in 1969. It’s part of a much larger, more cinematic story for us in a way that one random catastrophic season by another team will never be.”

Indeed, the Mets’ championship in 1969 has retroactively uplifted that ’62 team as well.

“To have won a world championship seven years later provides the perfect bookend with the historic futility,” said Mets broadcaster Howie Rose, who was eight years old watching the Mets’ debut season. “It all ties together. It’s all part of the heritage. ’69 is sweeter because of ’62. It’s just a nice piece of perverse symmetry.”

“To never have finished above ninth place and then to win it all in 1969, that narrative is a very heroic and comforting one for Mets fans,” said Gary Cohen, New York’s television broadcaster. “The White Sox breaking that record wouldn’t change that. However, I don’t want to see anybody lose 121 games because that’s a horrible thing for their franchise.”

Dave Bagdade wrote “A Year in Mudville: The Full Story of Casey Stengel and the Original Mets” about the ’62 Mets. He also happens to be a lifelong White Sox fan.

“I don’t want to see their record eclipsed,” Bagdade wrote in an email. “I love the idea that they were the worst baseball team of the modern era, but that they lost with personality and humor and that they remain one of the most loved teams of any era despite (or possibly because of) their record. The ’24 Sox are just a steaming pile of baseball ineptitude. They don’t lose with personality and humor. They just lose. I don’t want anything about this Sox team to be enshrined in baseball immortality.”

In response to an informal poll on X, which obviously skews younger, about three in four Mets fans did want the White Sox to break the record. Younger fans feel little pride in 120 losses.

Looking ahead to this weekend, I’m curious: Do you as a Mets fan want the White Sox to break the ’62 team’s record for most losses in a season?

— Tim Britton (@TimBritton) August 28, 2024

Greg Prince, who pens the popular blog “Faith and Fear in Flushing” and has written four books about the Mets, ultimately agrees with the majority.

“I’ve been charmed by all that went into creating 40-120 my entire rooting life,” Prince wrote in an email. “The legend of the 1962 club will endure no matter who holds the record. All that being said, hell yes, let somebody else lose more than my team. Plus, you know, history. Somebody setting a mark like this while we’re here to witness it is worth a dozen Danny Jansens facing off against another dozen Danny Jansens.”

Jay Hook, shown here on June 2, 1962, recalls looking at the roster and thinking, “Man, that’s a pretty dynamic list.” (Harry Harris / Associated Press)

There’s one other reason Hook and Anderson don’t want the record to be broken. Playing for the 1962 Mets is a part — a significant part — of their personal legacies in baseball.

Hook recorded the first win in Mets history; there’s a ball displayed prominently at Citi Field with his name written on it in large letters. Anderson signs almost all his autographs with “Original Met.”

“If you’d asked me this back in the mid-60s, I would have said I was so happy to get it over with and get out of there,” Anderson said. “But after 62 years now …”

Hook thought back to the Old Timers’ Day the Mets held in 2022. The club had asked him if he wanted to pitch, and the then-85-year-old suggested a first pitch instead. He worked out for weeks to get himself in shape, and then, in front of more than two dozen members of his family, he fired it to Mike Piazza on the fly.

“They had the best weekend going to New York and being at Citi Field,” he said of his family. “I’ve had more publicity because I was on that team. That’s survived.”

It will survive even if the White Sox fail to win 12 games over the final month of the season. If the ’62 Mets cede their long-held pedestal in the sport, their legacy, one that’s grown in fondness with each passing year, is secure.

“With the passage of time, it has become increasingly difficult to accurately portray who and what those Mets were and what they represented,” Rose said. “For those not of age when the Mets came about, they could not possibly understand what their impact was not only on baseball fans in New York but around the country.”

(Top photo from the Polo Grounds on June 20, 1962: Associated Press file)