Juliette Pavy’s documentary series explores the severe and lasting impacts of an involuntary birth control campaign led by Danish authorities in Greenland in the 1960s and 1970s. It examines the Spiralkampagnen, in which several thousand Inuit women and girls, some as young as 12 years old, had intrauterine devices implanted without their consent. The project traces the programme’s origins through to the present day, including the ongoing investigation by the Danish government.

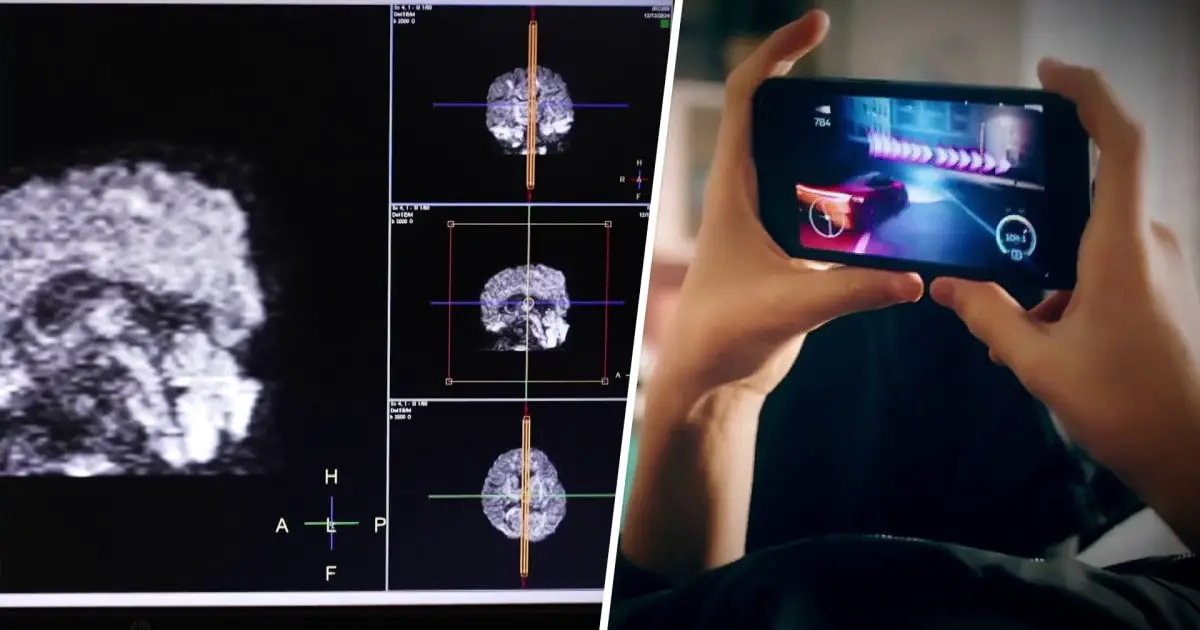

Placing the victims’ perspectives at the forefront, the narrative structure of Pavy’s project is shaped by difficult and important reflections on the collective trauma experienced by a community. The series uses a variety of photographic formats, from situating shots of the city of Nuuk and its clinical spaces to X-ray imagery and archive photographs of the young women involved, alongside recent portraits of victims, doctors who worked in Greenland during and after the programme, and the Danish parliamentarian investigating the Spiralkampagnen today.

-

Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, is located on the west coast and has a population of about 19,000.

Juliette explains how she discovered the story: “I was following the subject of Arctic women in the news, and in the daily press in Brittany I noticed a small AFP brief about the topic. I was very curious and I wanted to find out more. As I was already going to Greenland for another assignment, I followed up on the story, and began to meet with the women.”

Between 1966 and 1975, Greenlandic Inuit women were subjected to an involuntary birth control programme known as the Spiralkampagnen (“spiral campaign”). Led by the Danish authorities, nearly 4,500 intrauterine devices, otherwise known as coils or “spirals”, were implanted into Inuit women and girls, some as young as 12. Many of them say that the procedure was performed without their consent. The campaign was first widely publicised by a Danish podcast in spring 2022, and documents now prove that the authorities implemented the policy to reduce Inuit population growth. An official investigation has now been opened, which is set to conclude at the end of 2024.

In 2019, Naja Lyberth, a psychologist in Nuuk, told her story to a local newspaper. Following revelations of the existence of a Danish policy of forced contraception, she created a Facebook group that brought together other victims. “We have the right to own our bodies, and it is our human right to have children,” she said. Lyberth is trying to continue her fight for justice through international human rights organisations.

In May 2022, a Danish journalist, Celine Klint, discovered a document proving that Denmark had organised a policy of forced contraception for Greenlandic women in the 1960s and 1970s. These revelations led to an official inquiry into the campaign, which started in October 2022 and will run until the end of 2024.

After a school medical check-up, one of the victims, Jytte Lyberth, was sent to hospital and was asked to take off her clothes. She was never told what was going to happen. A few months later she experienced severe pain from the coil and returned to hospital to have it removed. Since then, she has been unable to have children.

In Nuuk itself, there are relatively few victims of the Spiralkampagnen compared with the total number of inhabitants. Aviaja Siegstad, who was a gynaecologist in the 1990s, thinks this may be due to the capital’s mixed population. Local doctors may also have been probably more resistant to the contraceptive policy.

Siegstad would regularly see women with fertility problems only to discover that – unbeknown to them – they had had an IUD or “spiral” fitted. This happened quite often, but her department put it down to the work of unscrupulous doctors. They had no idea it had been a political choice. She said: “For me, the crime in this is the political decision, and the systematic use of prevention to reduce a population.”

These IUDs were far too large and unsuitable for the bodies of young teenage girls. In addition to the pain and bleeding, the spirals sometimes caused serious infections that have made some victims permanently sterile.

One gynaecologist who became chief of the village of Maniitsoq in the 1970s said: “Spirals were what we had, what was available to us … The instruction was from the Danish authority. There was a social problem in Greenland [and] many young women were having their first child at the age of 15 or 16. It’s so easy to see it afterwards. The doctors thought they were doing something good, but it was terribly stupid … I wasn’t a particularly good chief. I have no doubt about that. I could have done much better. I regret it today.”

The Danish politician Trine Pertou Mach is a member of the leftwing government and responsible for Arctic development issues. She is closely following the current investigation. She has been making it her role to remind the government that this inquiry was promised, and to urge them to act on it – in particular, by validating the timetable and following the taskforce’s deadlines.

The birthrate halved in the years after the Spiralkampagnen.

Monica Allende, the chair of the 2024 professional competition jury, said: “The jury lauded Juliette Pavy’s empathic portrayal of her subjects, capturing them in a manner that is both dignified and profoundly intimate, thereby highlighting her exceptional talent. Pavy’s dedication to exposing the stark realities faced by marginalised communities, coupled with her compelling narrative approach, has not only earned her the prestigious recognition from the Sony World Photography awards but also underscores the jury’s belief in her potential and the importance of supporting her career trajectory.”