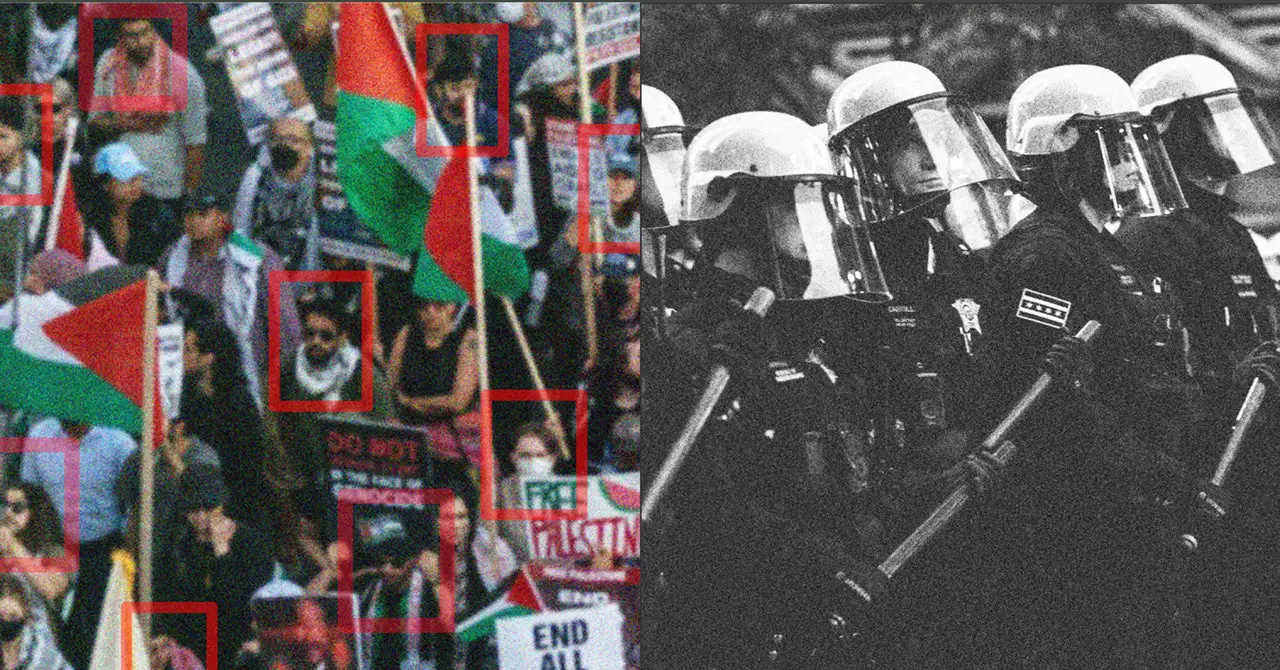

As thousands took to the streets during August’s Democratic National Convention in Chicago to protest Israel’s deadly assault on Gaza, a massive security operation was already underway. US Capitol Police, Secret Service, the Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Investigations, sheriff’s deputies from nearby counties, and local officers from across the country had descended on Chicago and were all out in force, working to manage the crowds and ensure the event went off without any major disruptions.

Amid the headlines and the largely peaceful protests, WIRED was looking for something less visible. We were investigating reports of cell site simulators (CSS), also known as IMSI catchers or Stingrays, the name of one of the technology’s earliest devices, developed by Harris Corporation. These controversial surveillance tools mimic cell towers to trick phones into connecting with them. Activists have long worried that the devices, which can capture sensitive data such as location, call metadata, and app traffic, might be used against political activists and protesters.

Armed with a waist pack stuffed with two rooted Android phones and three Wi-Fi hot spots running CSS-detection software developed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital-rights nonprofit, we conducted a first-of-its-kind wireless survey of the signals around the DNC.

WIRED attended protests across the city, events at the United Center (where the DNC took place), and social gatherings with lobbyists, political figures, and influencers. We spent time walking the perimeter along march routes and through planned protest sites before, during, and after these events.

In the process we captured Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and cellular signals. We then analyzed those signals looking for specific hardware identifiers and other suspicious signs that could indicate the presence of a cell-site simulator. Ultimately, we did not find any evidence that cell-site simulators were deployed at the DNC. Nevertheless, when taken together, the hundreds of thousands of data points we accumulated in Chicago reveal how the invisible signals from our devices can create vulnerabilities for activists, police, and everyone in between. Our investigation revealed signals from as many as 297,337 devices, including as many as 2,568 associated with a major police body camera manufacturer, five associated with a law enforcement drone maker, and a massive array of consumer electronics like cameras, hearing aids, internet-of-things devices, and headphones.

WIRED often observed the same devices appearing in different locations, revealing their operators’ patterns of movement. For example, a Chevrolet Wi-Fi hotspot, initially located in the law-enforcement-only parking lot of the United Center, was later found parked on a side street next to a downtown Chicago demonstration. A Wi-Fi signal from a Skydio police drone that hovered above a massive anti-war protest was detected again the next day above the Israeli consulate. And Axon police body cameras with identical hardware identifiers were detected at various protests occurring days apart.

“Surveillance technologies leave traces that can be discovered in real time,” says Cooper Quintin, a senior staff technologist at the EFF. Regardless of the specific technologies WIRED detected, Quintin notes that the ability to identify police technology in real time is significant. “Many of our devices are beaconing in ways that make it possible to track us through wireless signals,” he says. While this makes it possible to track police, Quintin says, “this makes protesters similarly vulnerable to the same types of attacks.”

The signals we collected are a byproduct of our extremely networked world and demonstrate a pervasive and unsettling reality: Military, law enforcement, and consumer devices constantly emit signals that can be intercepted and tracked by anyone with the right tools. In the context of high-stakes scenarios such as election events, gatherings of high-profile politicians and other officials, and large-scale protests, the findings have implications for law enforcement and protesters alike.